DRAKENSBERG AND CAPE TOWN

Protea cynaroides, King Protea

Main Aims and Objectives of Bursary Recipient

● To increase knowledge of South African flora

● To increase knowledge of South African species suitable for cultivation in the UK

● To increase understanding of conservation projects abroad

● To increase understanding of how botanical gardens are managed abroad

● To learn propagation techniques for a variety of plants

● To share knowledge with the wider world of horticulture

Part 1 – Drakensberg

Weather: Sunny, 25 ℃

Altitude: 1,700 metres

After a long overnight journey followed by a domestic flight from Cape Town to Durban, our group arrived at the airport in time for lunch, met by our guide for the trip, Elsa Pooley. A well deserved lunch followed and we set off to Underberg in the Southern Drakensberg, a village on the edge of the Maloti Drakensberg World Heritage Park, where we would spend a couple of nights at the Cedar Gardens B&B.

I enjoyed taking in the surroundings as we drove to Underberg, it reminded me of the Scottish Cairngorms in a strange way. Green, fertile grasslands and forests with undulating mountains around every corner. Seeing the landscape for the first time cemented the translation of Drakensberg, which comes from the Africaans word “dragons” meaning dragonous mountains.

A pleasant drive took us to Cedar Gardens where we had time to freshen up before having dinner in a local restaurant just down the road which served all kinds of dishes, including delicious seafood. We each had individual lodges, dotted around the lovely gardens – I was fortunate enough to have a great room-mate for the entire trip, Gilly.

First view of Sani Pass

Weather: Sunny, 28 ℃

Altitude: 2,874 metres

We set off promptly in the morning after meeting our drivers – Stuart, Neil and Mondli – who would be taking us safely up Sani Pass to Lesotho, in 4×4 vehicles.

Sani Pass is world famous, the mother of all South African mountain passes, photos do not do it justice – the higher we climbed up the snaking gravel tracks, zigzagging through the awe-inspiring mountains, made the first full day of the trip one of the most memorable.

I can see why the Zulus call the jagged peaks of the Drakensberg Ukhahlamba, meaning “a barrier of spears”.

The Sani Pass road connects the KwaZulu-Natal town of Underberg with Mokhotlong in Lesotho. The beginning of our drive was slow as there were roadworks at the start of the pass; it is being tarred completely, going from dirt tracks to tarmac. This process will take five to ten years to complete and will open up Sani Pass to a vast new audience, boosting local tourism.

The roads were narrow with no guardrails, even though we were driving on the edge of the mountain we never felt unsafe, our group had unanimous faith in our drivers – they were unbelievably careful and intuitive of the road conditions.

Sani Pass

Protea dracomontana

Our ascent was full of plant stops, there was a plethora of flora to see. Even though I wasn’t familiar with most species in the Drakensberg, most of the plants we encountered are parents to many plants found in northern hemisphere gardens. Seeing proteas growing wild was a highlight throughout the trip, even more prevalent on our first day. Protea dracomontana was a firm favourite, a dwarf protea very common on grassy slopes over sandstone. It was interesting to observe how the flora changed with the geology as we gained altitude, the sandstone was replaced with basalt the further we climbed.

Kniphofia linearifolia

Buddleja salviifolia

Buddleja salviifolia was a very tactile plant, with woolly leaves that were velvety white underneath. Cussonia paniculata grew amongst the cliffs and contrasted with the proteas, its blue-grey foliage accentuating the vivid green landscape.

Cussonia paniculata

Corycium dracomontanum

Brownleea macroceras

Moraea brevistyla

Harveya pulchra

The most daring plant we saw was Gladiolus flanaganii, also known as the “suicide gladioli” – referring to the difficulties of getting close to this species. It has deep red flowers, and is found only hanging from crevices of wet basalt cliffs. It has adapted itself for pollination by the malachite sunbird. Due to its inaccessibility binoculars were very handy!

Binoculars were handy

Gladiolus flanaganii

Eucomis schijffii

Eucomis schijffii, a miniature eucomis found in wet rock faces, also enjoyed the company of cliffs – again we used binoculars to appreciate its dark red-purple flowers.

Dierama dracomontanum dominated a particular area of grassland, its habit very care-free in the harsh surroundings. This species is a good garden plant, with pink-coral flowers.

Brownleea macroceras was a striking orchid, growing on damp rocky grass cliffs. Cultivated as an alpine species, its sweetly scented white-lilac flowers have an attractively long spur and are pollinated by the long-tongued fly Prosoeca ganglbaueri.

Dierama dracomontanum

Moraea brevistyla was very delicate, also found in damp grassland areas. Its flowers were tiny, white-lilac blue above with purple beneath and striking yellow with brown spots on the inner tepals.

Zaluzianskya microsiphon was a gorgeous member of Scrophulariaceae, microsiphon meaning “small tube”. It is a perennial herb, found in rocky grassland, with a long dense inflorescence – pink-red outside and white inside.

Disa cephalotes ssp. cephalotes was an orchid which had a scabious-like appearance, with a round, compact inflorescence bearing white flowers with purple-red spots on the hood. It was one of my favourite disas of the whole trip.

Zaluzianskya microsiphon

Pterygodium cooperi

Disa cephalotes ssp. cephalotes

Pterygodium cooperi was another orchid, found at higher altitudes below cliffs and on steep wet grass slopes. Its flowers were white, flushed pink with age, with a band of dark speckling within the hood. They had a sharp scent, an unexpected surprise when crouching down to sniff the inflorescence.

As we neared the summit the hairpin bends gave way to spectacular views, we were blessed with beautiful sunshine and scenery to match. A series of distinctive pinnacles on the main escarpment named the “Twelve Apostles” were iconic, this image instantly springs to mind whenever I reminisce about the Drakensberg.

More passport stamps were required at the Lesotho border control post, which meant we had reached the summit, before we made our way to our accommodation for the night at the highest pub in Africa – Sani Mountain Lodge. It is situated on the edge of the escarpment and has breathtaking views of the pass and mountains below – the atmosphere was amazing, quirky history and graffiti adorned the interior walls. It isn’t a cheap place to stay because it is the only proper accommodation at the summit, but for one night it was affordable. Elsa said we were lucky having such clear weather as the previous plant group she brought here had mist for the whole trip and could barely see the lodges let alone the view.

Just after we arrived at the lodge a group of bikers turned up, which pleased me. I am a biker and as soon as I saw Sani Pass I had an itch to hop on a motorbike and ride to the top…

A storm arrived as we were having dinner, thunder, lightning and monsoon rain for most of the night – a complete contrast to the day’s sunshine. Classic mountain weather to end our first day.

Weather: Sunny and cloudy, 25 ℃

Unfortunately the morning after our first day I awoke feeling very grotty, with virus symptoms – sore throat, headache, blocked ears and nose. Apparently the change in altitude can affect people badly and if a virus is lingering in your body chances are it will break out when the immune system is low and adjusting to altitude. Elsa said I wouldn’t feel better until we left Lesotho and went down the mountains but I pressed on and enjoyed the day.

Almost all the plants on the summit in Lesotho are endemic to the mountain kingdom, we saw different species from those of the previous day and spent the morning exploring the summit and beyond.

Botanising

Carpets of Helichrysum

A wildflower hotspot beside the road

Cotyledon orbiculata

Cotyledon orbiculata

Massonia echinata

Jeanette with Helichrysum adenocarpum

Helichrysum pagophilum

Massonia echinata was growing flush to the ground, peeking above the gravel – it is found in gravel patches over rock sheets, often at summit plateaus. The leaves are covered in soft prickles, green above and purple below.

Helichrysum adenocarpum had attractive flowers with glossy red-pink bracts, a good garden plant found naturally in grassland on moist slopes. One of our members, Jeanette, was perfectly poised resting on a rock with hoards of H. adenocarpum round her feet.

Cotyledon orbiculata was another inaccessible beauty, a succulent shrublet found on steep cliffs. It was easy to spot only thanks to its branched orange inflorescence, visited by sunbirds. Another popular garden plant.

Helichrysum pagophilum was a fantastic compact, cushion-forming dwarf shrub, “pagophilum” meaning “lover of crags”. Its leaves were overlapping, a huge rosette of grey silky woolly foliage. I could see it colonising every crack and crevice in my garden.

Berkheya cirsiifolia was a glowing example of Asteraceae, a stout perennial herb growing up to 1.5 metres tall. Found on moist grassy slopes, with soft hairy stems and leaves, very thistle like in appearance. The flowerheads were white-yellow, with very leaf-like bracts bearing spines.

Berkheya cirsiifolia

Crassula setulosa var. setulosa had small mats of leaf rosettes, found on damp cliffs and rocks. The flowers were in small terminal clusters, white petals with a distinct appendage and pink buds.

Papaver aculeatum was first seen up Sani Pass but a particularly good clump was seen today. It is found in rocky places, in scrub and among boulders in riverbeds, widespread in South Africa. It is covered in stiff yellow spines and hairs, orange-red flowers were especially eye-catching amongst the beige rocks.

Gladiolus saundersii is always found in extremely inaccessible places, the specimen seen at Lesotho required crossing a fast-flowing riverbed which I had to avoid – blocked ears and balance don’t go well together! A few members made the crossing and returned with successful photos which the rest of us enjoyed.

The flowers of G. saundersii are large, downward facing and bright red with white speckling on the lower tepals. They are also edible and eaten raw in salads, alas we didn’t have a taste-test.

Phygelius capensis was found near a stream but much easier to see thankfully. Its scarlet, tubular flowers were a welcome splash of colour in the stream gully where it was growing. Nearby was Cuscuta campestris, an annual parasitic plant also known as golden dodder. It consists mainly of leafless, smooth, yellow twining stems and was a tangle of tendrils smothering its host.

Gladiolus saundersii

Crassula setulosa var. setulosa

Papaver aculeatum

Phygelius capensis

We made our way back to Sani Mountain Lodge for a quick lunch before our descent down Sani Pass – going down was more of a white-knuckle experience than going up, at times it felt as though we were on the edge of the world. Helichrysum aureum was the highlight going down, its bracts shining golden-yellow in the sunshine.

● Greater Double-collared sugarbird

● Cape Rock Thrush

● Bush Blackcap

● Malachite sunbird (green)

● Cape Vulture

● Bearded vulture

Weather: Cloudy and humid, 26 ℃

Kniphofia gracilis

Watsonia confusa

Two Brunsvigia species were seen, the first B. undulata: a large inflorescence held on a tall erect stalk, covered in deep red flowers, was unlike anything we had seen on the trip so far. A world away from the alpine plants at higher altitude.

B. radulosa was very similar in habit, except its flowers were pink and leaves thicker and rougher, more prominent than B.undulata – both marvellous examples of Amaryllidaceae.

Brunsvigia undulata

Dierama latifolium

Watsonia confusa

Brunsvigia undulata

We stopped for lunch in a shopping village. Elsa uses its cafe regularly for her tours as it is friendly with a good menu choice and books for sale. I hadn’t had much of an appetite over the previous few days, however I saw something on the menu which truly delighted me – a gluten free pizza! I’m coeliac and the gluten-free diet has become popular in the past couple of years which is great for me as it makes eating out easier and more enjoyable. It was definitely one of the best pizzas I’ve ever tasted, it gave me a buzz for the rest of the day.

Before we reached Giants Castle we had one last stop, for Dierama latifolium. It was growing in clumps in the open grassland, hard to spot the waving stems at first but the closer we went the more plants we saw. Its habit has a very lyrical quality, the pale pink flowers moving to the tune of the breeze.

Giants Castle is situated on a grassy plateaux on the ridge of a deep valley below the sheer face of the high Drakensberg. The reserve was established in 1903 and is 34,638 hectares in extent, forming part of the Ukhahlamba-Drakensberg Park World Heritage Site.

We arrived in good time and freshened up in our individual thatched chalets before dinner in the main building. The surroundings were very peaceful, with views of the 3,000 metre escarpment around us however we were warned to keep our doors and windows shut at all times because the local baboons can be very territorial. Luckily they didn’t disturb us.

Giants Castle

Weather: Warm and cloudy, 24 ℃

Altitude: 1,600 metres

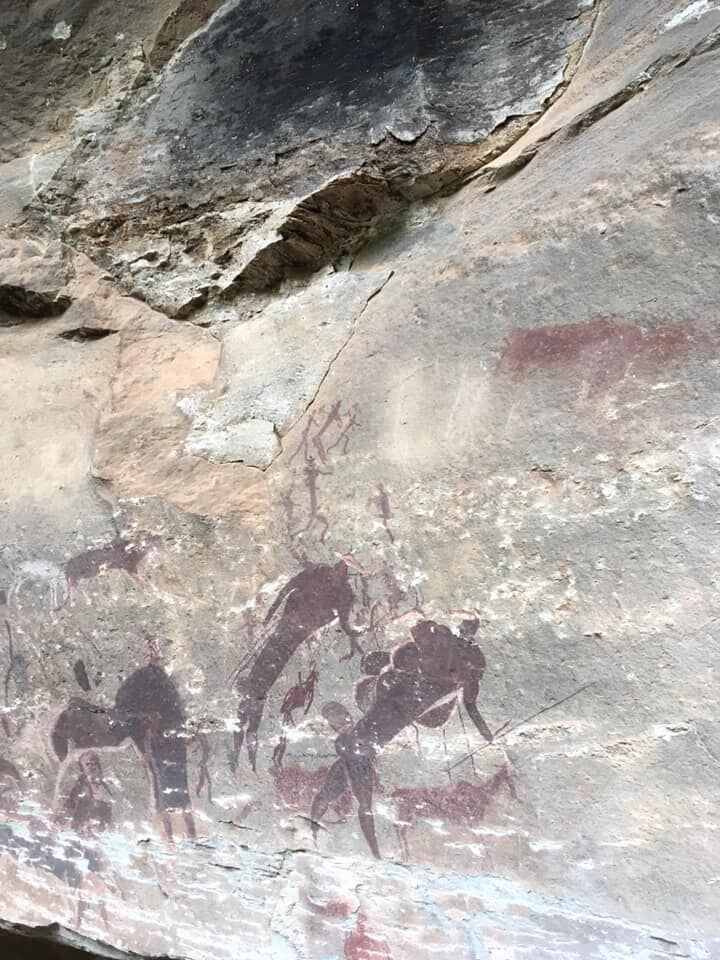

Bushman rock art

Elsa told us of a traditional African remedy to cure blocked sinuses: stuffing the leaves of Artemisia afra up the nose, I had to be the guinea pig and try it. My nose streamed after having the leaves up my nostrils for ten minutes, so it did work. One particular helichrysum we saw, Helichrysum hypoleucum, is grown successfully at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. It’s bizarre to think I saw it in the wild before seeing it in cultivation – usually it is the opposite. Its bright yellow flowers were similar to Helichrysum umbraculigerum, however the inflorescence of the latter looks umbrella like when turned upside down – a fun identification tip.

I was feeling much more myself today. We had a fabulous walk to the Main Caves and back, it was only a few kilometres but we stopped frequently for plants and had a guided tour at the Caves of the Bushman rock art.

Protea caffra was the dominant vegetation, decorating the valleys the deeper we went into the wooded areas. It is the most widespread Protea species in South Africa. Some specimens were flowering, with bright pink or cream bracts. On some of the older trees the bark was very thick and fissured, almost like cork oak (Quercus suber).

Streptocarpus gardenii

The writer with Artemisia afra

Stenoglottis fimbriata

Once we entered the montane forest around the caves we came across hoards of Streptocarpus gardenii, much to my delight. Streptocarpus were one of the first houseplants I started growing and still grow to this day – my plants at home paled in comparison to their wild cousins however. They mainly colonised the mossy damp rocks, pale violet flowers complementing those of the orchid Stenoglottis fimbriata, which were lilac-pink. A winning combination, an idea to take away and replicate in a miniature stumpery at home maybe.

Seeds of Kiggelaria africana

Psammotropha mucronata

iggelaria africana, the wild peach, was in the forest area near the caves. Its fruits were on the ground, rough and knobbly with shiny black seed in a red coating. Another tree in the same area was Olinia emarginata, with striking brown-yellow bark, flaky and tactile.

The guided tour of the caves and Bushman art was a great insight into this otherwise lost culture. No one knows exactly how old the paintings are, but the oldest are probably more than 500 years old. It was hard to comprehend how they could be so well preserved.

The Drakensberg is one of the richest rock painting areas in the world, with spectacular images. Most of the artists were hunter-gatherers who are often called Bushmen or San. Archaeological excavations of this shelter at Giants Castle show that hunter-gatherers lived here from at least 5,000 years ago until the 19th century. The materials used in the paintings are all local; blood, rock or soil rich in rust (ferric oxide) provide reddish brown. Charcoal provides the black, while white is created with bird droppings or clay. Melted beeswax or egg-white was used to mix with the pigment to make the paint but the Bushmen must have had a secret ingredient that made the paint last so long! They probably used the hair of the black wildebeest mane or tail attached to a reed as a paintbrush and pointed bones when they needed fine definition.

Members botanising

Chlorophytum krookianum

The paintings gave us a sort of picture-book of the past history and told a lot about how these people lived and what they considered important. Most of the paintings were of animals. The eland were drawn big and important, signifying how much they meant to the Bushmen – it was the most important food source and there were more pictures of eland than any other animal. Some researchers once thought that the art was simply decorative and a record of daily life. Today we know that hunter-gatherers did not separate their religious and everyday beliefs and activities rigidly, and the art shows these beliefs in a complex way. I enjoyed seeing the cave art immensely, a good cultural excursion to break up the botanising walk.

Disperis fanniniae

We spent a few hours before dinner completing our “plant homework”. This is an activity which Elsa offers to do with all her plant groups. It involves sitting down together and going through a printed list of all the plants mentioned in Elsa’s Mountain Flowers book and marking down which plants we saw on which day, which was tremendously helpful. It saved getting my notebook out every minute during our walks as I knew we would identify the plants we saw each day later on and thus making identifying photos easier too. The plant homework happened most evenings. The full list can be viewed at the end of this report.

I will finish with a saying found on one of the rocks during the morning’s walk:

“Climb the mountains and get their good tidings.

Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into the trees.

The winds will blow their freshness into you, and the storms will give you their energy;

while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.” – John Muir

Travel day: Giants Castle to the Cavern

Weather: Sunny, 32 ℃

Xerophyta viscosa

We left Giants Castle and journeyed to the Cavern, about two hours drive away nestled into the foothills of the Northern Drakensberg, in the Amphitheatre World Heritage Site (adjacent to the Royal Natal National Park).

Just before we left Elsa showed us a fantastic clump of Xerophyta viscosa, growing at the top of a steep rocky area at the back of one of the chalets. Some of the group scrambled up to get a closer look. The deep mauve-magenta flowers, lightly speckled black, were worth the early-morning exercise.

Once on the road we had some memorable plant stops, including a short trek to the bottom of a river valley to see Hesperantha coccinea growing by the water’s edge. Seeing a very familiar garden plant in its natural setting was a joy to behold.

Persicaria lapathifolia grew alongside the hesperantha, a widespread annual herb. Salix mucronata ssp. woodii had short yellow flower spikes, a pretty willow. Berkheya setifera was as cheerful as a sunflower in the sunshine, bright golden-yellow flowers looking picturesque against the clear blue sky.

Hesperantha coccinea

Persicaria lapathifolia

Salix mucronata ssp. woodii

Berkheya setifera

We arrived at the Cavern with enough time to settle in and look round the beautiful gardens. It is a resort and spa, the most luxurious accommodation we had in the Drakensberg. We even had WiFi which everyone made the most of! The Cavern is nationally recognised by KwaZulu Wildlife as a Site of Conservation Significance for conserving rare, endangered and endemic species. It has many walks and trails through nearly 3,000 hectares of natural mountains. It has been run since 1941 by three generations of the same family, and the whole set up was well organised.

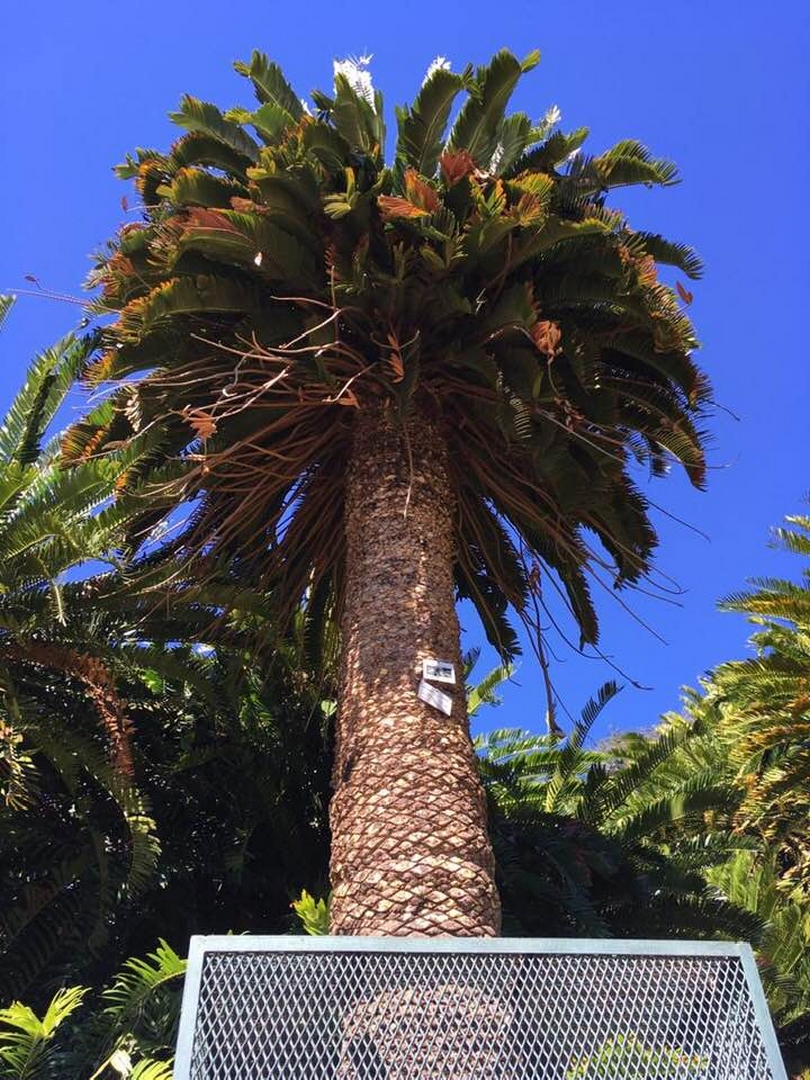

Some notable plants in the gardens included Podocarpus falcatus, a huge tree which gave splendid shade: Kniphofia northiae, named after Marianne North: and an iconic cycad, Encephalartos ghellinckii, which is endemic to South Africa.

Eulophia welwitschii

Xysmalobium undulatum

Encephalartos ghellinckii

Schizoglossum atropurpureum ssp. atropurpureum

View of the Drakensberg

Royal Natal National Park

Weather: Sunny then storms and rain, 24 ℃

Altitude: 1,700 metres

The park has an interesting history dating back many years. In 1836 while exploring Basutoland, two French missionaries first discovered Mont-Aux-Sources, literally the mountain of sources (of the rivers). In 1908 the idea of establishing a National Park in this area was conceived, and the territory was explored by Senator Frank Churchill, General Wylie, Colonel Dick and Mr W. O. Coventry.

Recommendations were put forward but it was not until 1916 that the Secretary of Lands authorised the reservation of five farms and certain Crown Lands, totalling approximately 8,160 acres, and entrusted it to the Executive Committee of the Natal Province – in September 1916 the National Park came into being and an advisory committee was appointed to control the park.

Exploring

Protea caffra

The local weather forecast predicted a storm at midday so we felt confident in trekking a short part of the Tugela Gorge, within the Royal Natal National Park, to see the views and flora, however the rain started earlier than anticipated…. Then came the thunder and lightning! It was a total contrast to how it had been just an hour or so before. We had been very fortunate up to this point, as the previous storms had arrived in the night and cleared by the morning.

We saw Ilex mitis, the only African holly and a particularly huge Protea caffra which also had near-perfect flowers. The proteas are larger in the Drakensberg than in the fynbos, due to summer rainfall. In the Western Cape they have winter rains, hence smaller shrubs.

Helichrysum cymosum was seen everywhere on the slopes, a silver ground-cover. Africans burn it to keep the spirits of ancestors safe.

A cute fern was Pellaea calomelanos, common in South Africa. It had eye-catching, grey-green foliage, found in rock crevices. Monsonia attenuata was in tight bud as there was no sun but this meant its distinctive purple net-veined marks on the underneath petals were visible, contrasting with the white flowers.

Clumps of pure white Galtonia candicans rose straight out of the bracken vegetation, it can grow up to 1.5 metres tall. Galtonias are endemic to South Africa, and have been cultivated in Britain since 1862 – an excellent garden plant.

The surroundings became more atmospheric, with the mountains shrouded in mist, and the rain getting heavier and more dramatic by the minute. We did get very wet but I enjoyed it; seeing and feeling the rains in the humid wilderness made me appreciate the sensational flora which grows in these conditions even more.

We had shelter for a short while in the forest, it was here we saw Begonia sutherlandii and Streptocarpus pentherianus. The latter had flowers smaller than my fingernail, absolutely adorable. B. sutherlandii had several red-orange flowers, it’s easy to see why it’s such a popular container and garden plant.

Ledebouria cooperi was strewn over some of the pathway, the debris was most likely caused by baboons as they like to eat the bulbs.

Unfortunately we didn’t make it to the Ampitheatre as the monsoon rain made the pathways too slippery to continue. Alas, circumstances were beyond our control.

Pellaea calomelanos

Monsonia attenuata

Galtonia candicans amidst the vegetation

Begonia sutherlandii

An early arrival at the Cavern meant the afternoon was free for us to relax, I was tempted to try out the swimming pool but I’d already had an outdoor shower that day. The rain eased off by 4pm, meaning I could enjoy the gardens again and explore the vast interior of the resort, which included a games room and wine cellar.

One of the group members, Cathy, had celebrated her birthday the previous day without telling us. She didn’t get away with it however. The staff at the Cavern danced and sang happy birthday around the table at dinner, it was a joyous performance.

Ledebouria cooperi

Streptocarpus pentherianus

Travel day: the Cavern to Witsieshoek via Golden Gate Highlands National Park

Weather: Cloudy, humid 20 ℃

Cliffs of Golden Gate Highlands National Park

Pelagonium luridum

It was a sparse day for flora but a rich one for fauna, including our first zebras and ostriches of the trip – it felt as though we were on safari. Other wildlife included black wildebeest, springbok, blesbok and eland antelope, as well as many birds we couldn’t identify.

We saw the wildlife from a distance, however binoculars turned the dots into detailed creatures. I enjoyed seeing the eland the most as it made me connect to the cave art seen at Giants Castle and gave the paintings new meaning.

We said goodbye to the Cavern and set off for Witsieshoek (pronounced vit-see-hook) Mountain Lodge, a small inn run by the local community in collaboration with a Peace Parks (trans-frontier) company.

We passed the impressive Sterkfontein Dam (third largest dam in South Africa) before entering the Golden Gate Highlands National Park, currently the only grassland National Park in South Africa. The name ‘golden gate’ originates from the two cliffs that face each other on either side of the road: at sunset, the yellow sandstone becomes a rich gold colour.

Members viewing wildlife

Hibiscus trionum

We stopped at a shopping village for lunch, at a place called the Highlander – it had very good food, with big portions and tasty Illy coffee. I didn’t buy anything in the shops but it was fun to wander around and be a tourist for a bit.

Plant highlights were a hibiscus and pelargonium, both seen in the same grassland area. Pelargonium luridum had one solitary inflorescence, with pale pink-cream flowers. Hibiscus trionum is an annual, widespread in scrub grassland, with creamy yellow flowers bearing a deep red centre.

All around the park we saw black stripes on the rocks, which are areas where water seeps out of the rocks. Minerals from the top basalt layer (manganese dioxide) are carried in the water and these stain the rocks black. The water enables organisms like algae and moss to live there as well

We arrived at Witsieshoek in the evening, which has spectacular views of the mountains apparently but we never saw them – we brought the mist and rain with us instead. After dinner I had an early night, as I wanted to be alert and enjoy our last hike in the Drakensberg the next day.

Witsieshoek and Sentinel Peak

Weather: Wet, windy, humid 20 ℃

Altitude: 2,400 metres

Gladiolus crassifolius

I awoke early and had a short botanise in the meadow at the back of our lodge before breakfast – the sky was almost clear at 6 am but within 15 minutes the cloud had come in again. I managed to spot a lovely little gladioli covered in raindrops – Gladiolus crassifolius. Its flowers were small and turned to one side, a soft pink colour.

Two 4x4s took us to our starting point, the Sentinel car park, 13 kilometres from Witsieshoek. We spotted plants on the way, particularly nice specimens of Leonotis intermedia, common on the ascent up the rocky hillside, with fabulous orange flowers in compact clusters.

Satyrium parviflorum had a spiked inflorescence of yellow-green flowers, only seen once before on our first day. Many of the plants seen today were also seen last week up Sani Pass and/or Lesotho, due to the similarities in altitude. It put our memories to the test, trying to remember the plants we had previously seen.

The views still eluded us, the higher we climbed the deeper the cloud became… we had all brought waterproofs, which came to good use because as soon as we stopped in the car park the rain came down. It was light drizzle at first and we were still enthusiastic enough at this point to persevere, however half an hour into the trek the rain became heavier and the winds stronger.

There was a lot to see on the pathway towards Sentinel Peak, we weren’t heading to the summit as there was plenty to see en route. We followed the narrow path along the cliff, not seeing more than five feet in front of us. It was a quicker trek than normal as we didn’t stop as often because it was impossible to photograph anything well in the adverse weather.

Satyrium parviflorum

Leonotis intermedia

Elsa really wanted us to get higher so we could see the nerines – we had lusted after them from the beginning of the trip, and we were so close now it seemed foolish to turn back. We blindly followed her and were immensely glad we carried on because ten minutes later we found Nerine bowdenii in full glory. A great specimen was on the edge of the path with more clumps colonising the base of the cliffs. The beautiful pink flowers were battered in the winds and rain but we didn’t care.

A group of Eucomis bicolor was glorious, growing en masse below the basalt cliffs, bobbing their wonderful densely packed “pineapple” shaped heads in the wind. Eucomis humilis was also spotted, tiny in comparison to E. bicolor which can get to one metre tall. It had a dwarf, tufty inflorescence but still attractive.

Eucomis bicolor

Nerine bowdenii

Eucomis bicolor amongst the rocks

Ironically as we made our way back to the car park the wind and rain eased slightly, enabling us to take in the surroundings better – still the views were just cloud. We had seen Zantedeschia albomaculata previously but not in such good condition as today. Its classic arrow-shaped leaves had one creamy-white cylindrical spathe emerging.

Gladiolus microcarpus

Zantedeschia albomaculata

We had a picnic lunch in the shelter of one of the buildings in the car park and started walking down the path until the drivers of the 4x4s met us on the descent. It was pretty cramped in the vehicles as only one driver turned up at first, so three of us were in the back and I was the fourth hanging on the tailgate – perfectly safe of course, we only went slowly over the gravel track. It was a surprisingly good position as my clothes dried in the breeze and I could see the upcoming views and plants perfectly.

Once we got further down the mountain the mist started clearing and the skies brightening, like walking out of armaggeddon into heaven. We were rewarded with some amazing views and plant life, Gladiolus microcarpus was a great find; hanging from a moist crevice in the cliffs, with a pendulous inflorescence bearing pink-mauve flowers.

Lobelia flaccida

Crassula sarcocaulis ssp. rupicola

Lobelia flaccida was a pop of colour on the rocks, blue flowers holding the raindrops well. Crassula sarcocaulis ssp. rupicola was a succulent shrublet found in damp rock outcrops at the base of the cliffs. Its branches had peeling bark, with needle like leaves and terminal heads of white flowers.

Hebenstretia dura had a slender, elongated inflorescence with white and orange flowers, good clumps in the damp grassland.

Hebenstretia dura

Our final find was Gladiolus ecklonii, we initially stopped to take in the view then saw it around our feet in the grass. It had silvery white flowers densely speckled red-brown; they close at night to re-open in warm sunlight. Luckily for us, the sun had burnt its way through the cloud. Otherwise the flowers would not have been open. It hybridises with G. crassifolius, which I saw earlier in the morning.

Weather: Cloudy and sunny, 25 ℃

Blazing sunshine greeted us when we stepped off the plane, much hotter than what we had been used to for the past ten days. It was a welcome warmth, the summer in the Western Cape is a world away from the Drakensberg. Charlie Ratcliffe, an accredited guide for the area, greeted us and drove us to our hotel, which is five minutes from Kirstenbosch. On the way we saw the local townships and shack houses, before entering the “other half” of Cape Town. It was upsetting seeing how real the racial segregation was, even 25 years after the Apartheid regime ended. Charlie said things are changing slowly but there are still racial disparities in land ownership and social effects of the regime which continue to this day.

The Vineyard Hotel is seriously plush. When we arrived we felt like refugees, sweaty, with backpacks and walking boots, while other residents looked glamorous in dresses, suits and heels. The interior was immaculate, with chandeliers in most rooms; my favourite soft furnishing were the cushion and chair covers with a ginkgo leaf print. For me the accommodation was over the top, I would have been happier with somewhere more basic (especially after seeing the townships driving from the airport), but it was all paid for, so we made the most of it.

I had time to wander round the gardens before dinner, which are a good size for an urban hotel, and very well laid out – having Table Mountain as a backdrop was exquisite. The restaurant was pleasant, meals other than breakfast weren’t included in this part of the trip and there was talk of trying out a restaurant in town instead of staying at the hotel to eat every night but, for our first evening, we were all happy to relax at the Vineyard.

Elsa stayed with her brother who lives in Cape Town and, as I was the only MPG Management Committee member on the tour I handled enquiries from group members and relayed messages to the group from Elsa, such as morning meeting times.

Weather: Sunny, 26 ℃

First view of Table Mountain

Kirstenbosch truly is an incredible garden, my first impressions of walking through Camphor Avenue into the open lawn area and seeing Table Mountain was unforgettable. Ceratotheca triloba, a wild foxglove, was beautiful flowering with kniphofias near the main lawn.

I wasn’t expecting the topography to be so varied, it was a good workout from the bottom of the Dell through the Cycad section up to the top Proteaceae and Fynbos beds. It was another sunny, clear day and the views were stunning from the top of the garden. There was a good balance between shaded areas and open spaces, with lots of seating available.

This “cuddle puddle” is found in the Dell, its proper name is Colonel Bird’s Path. In 1811, a few years after the British took control at the Cape, the southern half of Kirstenbosch was bought by Colonel Christopher Bird, who was then Deputy Colonial Secretary. He built this bird-shaped pool to collect the spring water and let it stand and clarify before being piped to the house. The water bubbles up from an underground spring at an average of 72 litres per minute, all year round – it’s good enough to drink.

Agapanthus inapertus ssp. pendulus ‘Graskop’

Kirstenbosch didn’t feel like a cultivated garden as much as other gardens I’ve visited because it blends into the surroundings of Table Mountain National Park seamlessly. As it was a Sunday it was busy with families and couples but, as the garden is so large, people weren’t on top of each other at all. I didn’t have trouble finding a free bench or quiet spot to sit and soak up the views and plants.

A plant I really want to try and source in the UK is Agapanthus inapertus ssp. pendulus ‘Graskop’, which is deciduous and more hardy in cold climates, making them ideal for cold frosty gardens that struggle to grow the “normal” evergreen agapanthus. It is a sought-after garden plant but not often available for sale, unfortunately. The cultivar ‘Graskop’ is named after the town in Mpumalanga nearby where it was collected by Kirstenbosch horticulturists in 1937. It can be seen growing wild in the grasslands in this area.

I had a random but lovely meeting with a couple near Mathew’s Rockery who just became engaged a few minutes before I walked past. We shared details about where we were from and what we were up to while drinking champagne for a good half hour, another memorable experience.

Encephalartos woodii

Fynbos path

Tree top walkway

Kniphofia species

Members in the conservatory

Andansonia digitata in the conservatory

Protea repens

Restio beds

Mathews’ Rockery was one of the earliest developments in the garden; when the aloes failed to thrive in the poor sandstone soils of the Koppie, these warm, north-facing slopes with granite-derived soil were chosen as the new site for the succulent garden. Every rock was brought here by sledge and mules, and manoeuvred into place by hand.

Euphorbia ingens was a huge euphorbia here, towering over the intricate maze of pathways. Nearby Calodendrum capense was a show-stopper, a tree with extraordinary blooms similar to Cleome flowers.

There were loads of small pathways leading to different sections, off the main path; it was fun to forget the visitors map and just wander on my own, discovering the Pelargonium garden and Braille Trail on the way to the cafe where we met up for a late lunch.

Gingko biloba

Some 90 per cent of pelargoniums are indigenous to South Africa, many of them are tuberous plants (eg Pelargonium longifolium), while others are deciduous succulents (eg Pelargonium crithmifolium) which survive in the arid regions of the country.

In the early days the Koppie, a natural sandstone outcrop, was called the Aloe Koppie, intended to grow and display aloes. In 1915 the paths were laid out, the ground prepared and the first plants planted. However the aloes failed to thrive here and were moved to Mathews’ Rockery. Arctotis venusta was a pretty member of Asteraceae in this area.

I ate far too much for lunch, a traditional South African dish of bobotie, consisting of curried minced meat baked with an egg-based topping – scrumptious! This was followed by a gluten-free chocolate mousse cake, I actually skipped dinner that night because I wasn’t hungry.

There was time for another hour or so in the garden before going back to the hotel. I enjoyed wandering through the Peninsula garden down to the Conservatory, and into the Gondwana Garden where there was a large Ginkgo biloba tree.

Water

Information regarding water use was interesting: the water at Kirstenbosch is not supplied by the City of Cape Town, the garden is irrigated by non-potable water from a 110 megalitre dam situated on the southern mountain slopes. Water comes from surface runoff and streams in Window Gorge and Nursery Ravine, most water is collected during the winter rainy season. Although the dam is full at the start of the summer dry season, the water supply is limited and it is a constant challenge to make sure the water lasts through the summer.

All drinking water is extracted from boreholes on the Estate that tap into the Table Mountain Aquifer, 60 metres below ground level. The water is stored in reservoirs where it is sanitized with Ozone to control randomly occurring biological activity, no chlorine or other chemicals are used. There were frequent water fountains around the garden, I refilled my water bottle several times during the day.

Some facts which opened my eyes included:

● A loo flush uses 12-15 litres of water

● A tap uses 20-30 litres of water per minute

● A shower uses 15-18 litres of water per minute

● A bath uses 159-200 litres

Baths weren’t allowed in the Vineyard, due to the current water crisis in Cape Town; when we had showers we put a bucket of water underneath to catch the excess water, it was shocking how quickly the bucket filled up. I grew up in a rural environment with a borehole so am used to being mindful of water usage but staying in Cape Town made me even more aware of it.

Weather: Sunny, 28 ℃

We were told of a devastating fire which happened New Year’s Eve in the Betty’s Bay area, started by a person who had too much to drink. They let off a flare which went sideways instead of upwards and, due to the extremely strong winds that night, the fire took hold and raged for a week. One person died from smoke inhalation and 30 homes were burnt. The fire stopped just before reaching Vicki and Robbie’s garden, as the wind suddenly changed direction.

The garden is dominated by a staggering collection of Mimetes, Mimetes stokoei was my favourite plant by far. It has been classified extinct twice since its discovery in 1922, only to be found in the wild again after an intense fynbos fire that burned through the Kogelberg in 1999 – just like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

Robbie’s modest but functional nursery area is where he raises plants from both cuttings and seed; everything has a purpose in the small but practical space.

Robbie’s mother was a propagator at Kirstenbosch, hence propagating is a family trait. Robbie is very focused on grafting Mimetes species and experiments with methods all the time; he’s never been successful germinating Mimetes seeds, so he sticks to grafting.

Vicky and Robbie Thomas’s garden with lots of Proteaceae

Other Proteaceae included:

● Leucospermum hypophyllocarpodendron

● Mimetes arboreus

● Mimetes capitulatus

● Mimetes chrysanthus

● Mimetes hottentoticus

● Mimetes saxatilis

● Protea aristata

● Protea nana

Robbie’s wonderful collection and passion for his plants was infectious, it was a highlight of the trip. Afterwards Vicki showed us her indoor art gallery, where she had artwork for sale. I bought a few small prints and cards, they were exquisite.

Harold Porter National Botanical Garden

More fire damage

Aloes recovering from fire damage

We walked through the gardens and part of the Disa Kloof walk, a 950 metre trail winding from the garden into the Disa Kloof, under shady trees to a waterfall where the disas bloom in summer. Due to the fire damage there were no disas in sight which was a real shame but you can’t have miracles everywhere.

The trees and shrubs were charcoaled sticks, underneath green bracken had sprung up – the first plant to appear after fire damage. The surrounding mountains were grey mounds, with a few succulents in the garden like Kumara plicatilis severely blackened but still alive.

Natural fires happen every 14 to 15 years and is needed for germination purposes for some species; it will be interesting to see what emerges after this fire, as it raged for so long and got to incredibly high temperatures.

Other plants noted:

● Berzelia stokoei

● Helichrysum foetidum

I dined outside the hotel this evening, with a few other members of the group. The Vineyard kindly gave us a complimentary ride into town and back, it’s safe to walk there in daylight but not when it gets dark. We ate in a fun Italian restaurant where I had another gluten-free pizza, I am a sucker for them!

Weather: Sunny, 30 ℃

The planting is focused on indigenous plants, particularly fynbos, incorporating many buchu species and ericas, of which a large selection of unusual varieties have been sourced from Kirstenbosch. The garden’s four sources of water include a natural perennial spring, a seasonal mountain river, as well as a borehole and agricultural water.

Dylan Lewis sculpture garden

Dylan has grouped the sculptures within the garden not as a response to a conscious plan but rather through a process that unfolded intuitively over many years, in which certain sculptures seemed to “gather” in distinct areas.

It was a ridiculously hot day, our guide, Hanley, was very good and stopped in the shade when talking about certain areas of the garden. We were given parasols to use while walking around the garden which was welcomed by the group. I felt the garden blended well with the landscape, and the sculptures of wild animals appeared extraordinarily alive, their expressions captured perfectly. Seeing leopards in an authentic setting with native planting made them come alive for me. Dylan is always adding sculptures so the garden constantly evolves; he also showcases other sculptors work in garden too.

Coleonema pulchellum, the confetti bush, was expertly cloud-pruned into vast mounds. A vivid, lush green when most of the planting was more subdued colours. Dylan was heavily inspired by the poet and writer Ian McCallum, there were several poems by him throughout the garden which I enjoyed.

The large bronze sculptures weren’t bronze at all, they were made from a type of foam material encased in fibreglass then covered with oxide paint. This stopped them from being too heavy to move and place in the garden and are weighted down on display stones to stop them blowing away.

● Celtis africana

● Olea europaea ssp. africana

● Scabiosa africana

● Pelargonium sidoides

● Vachellia sieberiana

Babylonstoren

Babylonstoren

Lagenaria siceraria aka calabash

Lunch was an experience in itself, the quirky menu wasn’t cheap but they had a farm-to-fork philosophy which meant everything served was seasonal and grown in the garden. All of the 300+ varieties of plants in the garden are edible or have medicinal value and are grown as organically as possible

Cycad collection

We had an hour or so to explore by ourselves, the sun was still beating down so I walked through the shaded areas where Clivia miniata was growing en masse, underneath extensive trained vines, and through a large section of prickly pears, Opuntia ficus-indica. Carissa macrocarpa had sweet-tasting fruits, Buddleja auriculata made a good hedge in between the various fruit and vegetable areas.

The Cycad collection was chosen by Lourens Eales for Babylonstoren from existing plant collections and was impressively terraced, leading out into one of the huge vineyard areas. I’m very glad I visited Babylonstoren, it’s a unique place which was different to the other gardens we visited.

Favourite sayings from Babylonstoren:

“Gardening offers a considerable amount of freedom, the refining influences of poetry and beauty, contact with intelligent and interesting people, and health and happiness to mind and body.” – Babylonstoren

“I don’t know how one can walk by a tree and not be happy at the sight of it?” – Prince Myshkin in The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Table Mountain and Stellenberg Gardens

Weather: Sunny, 28 ℃

Altitude at Table Mountain: 1,085 metres

We had an early start today, departing the hotel at 6.30 am to beat the queues for the Table Mountain cable car. Even though we had pre-booked our tickets for the 8.00 am slot it’s still a first come, first served basis according to who fits in the first cable car.

The cableway was officially opened to the public in October 1929, the first cable car with a tin roof and wooden sides carried only 20 passengers. Famous passengers include King George VI and the Queen Mother.

In 1997 a major upgrade and redesign took place and reopened with new revolving cars carrying 65 passengers.

In the cable car

Consisting of layers of Table Mountain sandstone and Cape granite formed by igneous and glacial action 520 million years ago, Table Mountain is at least six times older than the Himalayas, making it one of the oldest mountains in the world. The indigenous inhabitants of the Cape, the Khoekhoe, called Table Mountain “Hoerikwaggo” meaning “mountain of the sea”.

It was cloudy at first but the sun rose quickly. This was the first time we had been at the right angle to see the true meaning of Table Mountain – the summit was as flat as a table.

The mountain’s famous cloud “tablecloth” is a meteorological phenomenon that causes cloud to tumble down the mountain slopes like billowing fabric. This phenomena is known as “Kaggen’s Karos” after the San tale of how Kaggen, the mantis god, pulls a white karos (animal pelt) from his mountain cave to quench fires on the mountain. Moisture-laden air rises and cools as it is drawn in from the sea and over the mountains of the peninsula – often condensing into cloud. On Table Mountain this creates the familiar “tablecloth”; in fact a huge dew cloud from which more than twice as much water, in the form of mist, is deposited on the mountain than falls as rain each year. Of particular importance is the fact that much of this precipitation takes place during the months of summer drought at the Cape. Percolating down through the highly fractured Table Mountain sandstone, this input recharges the water-table with the result that springs and streams issue from the mountain year round.

We spent a few hours botanising around the summit, there was a varied amount of flora to see in a fairly small area. We used binoculars to identify some species over the cliff edge, including Watsonia borbonica with funnel-shaped magenta flowers and Crassula coccinea, bearing flat-topped heads of scarlet flowers. My favourite finds were the two disa species: Disa graminifolia had striking blue-violet flowers, with the tips of petals lime green. Disa ferruginea was disparate in comparison, with bright red-orange flowers clustered on one spike.

Crassula coccinea

Disa graminifolia

Disa ferruginea

Lampranthus falciformis

We spotted some wildlife too, the Table Mountain beauty butterfly (Aeropetes tulbaghia), a red-winged starling and, only very briefly, a rock dassie (Procavia capensis) – a strange little mammal.

Salvia africana-lutea had aromatic foliage, with pairs of golden-brown flowers. Chrysocoma coma-aurea, was a shrublet laden with yellow flowers which had a button-like appearance.

Lampranthus falciformis was a very cheery member of Aizoaceae, carpeting the rocky ground with lilac-mauve daisy flowers. A noteworthy erica was Erica abietina ssp. abietina, with large, sticky tubular red flowers.

We also saw many king proteas, Protea cynaroides, from a distance, dotted along the side of the mountain. We caught the cable car down, it was just as much fun as going up!

Athol McLaggan, the head gardener, showed us round, giving us a very informative tour. Stellenberg is one of the Cape’s most important historic houses, unique in that it has remained largely unaltered since it was built in the 1740s. The same family has lived here since 1953, they have endeavoured to preserve and enhance its classic beauty.

The gardens are four acres, with one full-time gardener per acre. The white border was inspired by Sissinghurst, only off-whites and creams were used in the planting as pure white colours are too harsh in Cape Town due to the high light levels. Zephyranthes alba worked well at the front of the borders, flowers similar to species tulips.

The herb and vegetable garden were relaxing areas, with fragrant plants like Murraya koenigii, the curry leaf tree, and ornamental plants like Hibiscus ‘Canary Island’ and Pelargonium tomentosum.

The Cape cannot produce barrels of wine as the climate is too warm for English oaks (Quercus robur) to survive – they grow too quickly and the wood becomes unusable for timber. Turkey oak (Quercus cerris), pin oak (Quercus palustris) and water oak (Quercus nigra) are much happier here, hence the young plantings of these species at Stellenberg.

The Herb Garden

Two roses were especially pretty, Rosa ‘Madame Alfred Carrière’ and ‘New Dawn’, the latter covering a pergola wonderfully. Apparently roses used to be planted at the end of a line in vineyards, as the colour of the rose indicated whether the grapes were red or white, helpful when dealing with unskilled labour.

Hibiscus ‘Canary Island’

Members in the White Garden

Hydrangeas do very well in Cape Town as the cool moisture from the ocean suits them; at Stellenberg they are also fed with nitrogen followed by a rose feed once the growing season starts. Hydrangeas are known as the Christmas Rose because they flower in December and are used in seasonal, festive displays. Once the leaves start to fall from the deciduous trees they are blown straight onto the hydrangea beds, to act as a natural leaf mould. It also saves time picking up tons of leaves.

Elsa was on her way to Woolworths, South Africa’s equivalent to the UK’s Marks and Spencers, so she gave me a lift which was fortunate.

As it was our last full day of the trip for everyone apart from myself, I organised a farewell meal for us at the Vineyard and invited Elsa, her brother William and his wife Winifred to join us – the rest of the group thought it was a great idea, the hotel were very accommodating and even gave us a private room upstairs to dine in. It was a great way to say goodbye and thank you to the whole group for their brilliant company over the past few weeks. Being a small group meant we had bonded very well, it was going to be strange being without them for the rest of the trip.

Weather: Sunny, 27 ℃

The historical clock tower was a good feature, three storeys high with red bricks and pointed Gothic windows. The clock itself was imported from Edinburgh and became a landmark as soon as it was completed in 1882 as the first Port Captain’s office.

I would like to thank the Mediterranean Plants and Gardens Bursary Committee, RHS Bursaries and the Merlin Trust for granting me the funding which enabled me to go on this trip. Without this generous assistance being part of the trip would not have been possible, for which I am extremely grateful.

I would also like to express my great appreciation to Mediterranean Plants and Gardens and Elsa Pooley for organising and leading a truly amazing trip.

My heartfelt thanks go to everyone else in South Africa who helped make the trip run smoothly, including our Cape Town tour guide Charlie Ratcliffe, our coach driver Praveer and drivers for Sani pass, local garden guides and B&B owners. The trip would not have been as enjoyable without their warm welcome, generosity and enthusiasm.

A final message of thanks goes to the other trip participants, for being joyous, engaging and humorous company. Special thanks go to Jorun Tharaldsen, Celia Jones and Cathy Rollinson for being unofficial tour photographers and providing photos of me for this report.