Garden design in Greece and the Mediterranean

ONE WEEK COURSE, TUESDAY 26 OCTOBER TO TUESDAY 2 NOVEMBER 2021

SOUTH PELION, GREECE

FROM BURSARY RECIPIENT: SHARON HORDER

Objectives

• To develop an understanding of how to put together a basic garden design

• To learn how to develop my design ideas into plans that could be used by gardeners and garden users

• To improve my knowledge of Mediterranean plants

Expectations and what I was hoping to learn on the course

I made a career change into horticulture about six years ago and, although I have completed the RHS Level 2 Diploma and the Professional Gardeners’ Guild three-year traineeship, I hadn’t yet received any formal training in garden design. I currently work full time as a gardener at Merton College, University of Oxford and, while garden design is therefore not something I need to do on a daily basis, it’s an area of the horticultural profession that I would like to know more about and have some skills in. At Merton, we change bed and border displays on a regular basis, and I felt that a better knowledge of how to design garden spaces was something that could feed into my work there.

In addition, I have long had an interest in Mediterranean and drought-tolerant plants and gardens. At Merton, a variety of sheltered and walled areas allow us to grow a diverse range of Mediterranean plants, and so I’m always keen to improve my knowledge of Mediterranean flora. I also believe that with our changing climate, drought-tolerant planting is something that I should always be mindful of in my day-to-day work as a gardener.

It was with this background that I signed up to a course entitled “Garden design in Greece and the Mediterranean” taking place in the village of Lafkos in the South Pelion in Greece. The one-week course was designed to give participants knowledge of the foundations of garden design, and of how to create a garden in the Greek or Mediterranean context. It also aimed to enrich participants’ knowledge of Greek flora and the Mediterranean landscape, through visits to local landscapes and gardens.

My main hope for the course was that I would develop an understanding of how to put together a basic garden design – essentially learn how to look at an outdoor space, analyse it and work with those who use it to create a beautiful, practical and realistic garden design. I also hoped to learn how to develop those ideas into plans on paper that could be used by gardeners and garden users to bring an idea into reality. My other hope was that I would improve my knowledge of Mediterranean plants, by seeing them growing in a native setting, and also by seeing how they are used in private and public gardens in Greece.

The course location and teaching

View of the Pagasetic Gulf from the hotel

This trip was my first to Greece, and I knew little about the South Pelion region before I arrived. On the day of arrival, I met my fellow course participants. Due to the pandemic, numbers were low and we were a group of only four, all staying in a local hotel which was hosting the course. The three other participants were all British, two of whom lived in the South Pelion area and had an interest in improving their own gardens, and one who was a gardener living and working on Crete.

On our first full day, we had a chance to explore the local village which sits high in hills above the Aegean Sea with views of the Pagasetic Gulf. The old village remains car-free and the whole area has a network of medieval donkey paths (kalderimia) crossing the landscape which are still widely used and make the area a great place for hiking.

A kalderimi

This tour of the village was a great introduction to typical private gardens in the area. Many of the village houses had small courtyard gardens, where plants in pots, small trees and climbers were a key feature. Popular climbers were Trachelospermum jasminoides, Bougainvillea spp. and Parthenocissus spp.; small trees in these gardens were Punica granatum (pomegranate), Pittosporum tobira grown as a standard and various citrus; and common pot plants were Cyperus involucratus, Tradescantia pallida, pelargoniums and begonias.

Courtyard garden in Lafkos village

Pittosporum tobira grown as a standard

After this introduction to the local area, we met the course tutor and started our classroom sessions. The course was led by Lena Athanasiadou, a horticulturist and landscape architect from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. We had six full days of teaching and practical exercises, which were mostly classroom-based with a handful of excursions to visit local areas and gardens.

Our first day of teaching was a very interesting look at the plants common to Greece, including how well they grow in different parts of Greece, whether they are popular in private gardens or public parks, and any other points of interest such as whether they suffer from any pests or diseases. I found it fascinating to compare how many of these plants I had seen in other parts of the Mediterranean, and particularly, how many we grow at Merton.

We then had a session on the key characteristics of the Mediterranean garden, particularly the Greek garden, a session that encompassed history, culture, religion and changing trends. This led onto a lecture about the Greek landscape, and the vast variation that occurs across it from east to west, north to south and at different elevations. Everything from beaches to plains to mountains can be found across the country.

Olive grove outside Lafkos

Beachfront at Medina

View across Lafkos hillside

The garden design content

On our second day, we got down to some practical garden design exercises. Our starting point was an exercise on scale – how to create a scale drawing, and how to convert designs from one scale to another. We were given a very basic garden design, and had to convert it into 1:50, 1:100 and 1:200 plans on millimetre paper. For me, this was a great refresher on scales and a good way of becoming familiar with the tools we would be using for the week, such as scale rulers, millimetre paper and sketching pencils.

Scale drawing exercise

After this exercise, we considered the starting points for creating a garden design for a client – carrying out an analysis of the existing landscape and evaluating the requirements of the client. Lena taught us to think of landscape analysis in four categories: identity, anthropology, environment and perception.

- Identity: the location of the landscape; its character; any connections with other areas; the history and culture.

- Anthropology / humans: the functions and uses of the existing site; roads and paths; buildings; benches, lights and other equipment; infrastructure such as pipes and taps.

- Environment: the site’s topography; hydrology (where and how does water collect, does it sit stagnant?); soil; vegetation (weeds as well as intentional plants); orientation and micro-climates; signs of wildlife.

- Perception / use: views in and out of the landscape; the feeling of the place; sounds and smells, the true use of the garden (including parts that don’t get used); and how people move around it.

We were taught the importance of collecting this information through several in-person visits to a landscape before any design is put together. The information can be collected by taking photos, sketches, notes and obtaining any existing plans or surveys of the landscape.

In addition to visits to a site, a lot of useful information to inform a garden design can be obtained from a client questionnaire. This ideally would come before any plans or designs are drawn up, and may be more of a dialogue with the client than a one-off interaction. Lena pointed out numerous pieces of information that a questionnaire could ask for, from the basics about the infrastructure and services on a site through to allergies of garden users, pets that use the garden, how they want to use the garden and how they want it to feel (such as private, exciting, calm etc.). Here we were taught that it is just as important to ask what a client dislikes as what they like – for example, colours they don’t like, hard landscaping features that they wouldn’t want, areas of the garden they don’t currently use – as this can be highly informative in terms of being able to create a garden that will be loved and fully used by the client. In addition, this is the opportunity to find out how the garden will be maintained, such as who will be doing the maintenance, how much time will they give to this, and what budget will be available for maintenance after the initial creation of the garden.

Following the teaching of these key preliminary processes in garden design, we were then assigned a task that we would complete over the rest of the week. We were tasked with creating a garden design for a hypothetical garden in Greece. Our brief was:

to create a garden for a couple in their 40s with two children aged five and seven and a medium-sized dog. Their wishes are for a vegetable garden near the house, a herb garden, and a seating area with a pergola. Their plot is 20m wide x 25m long.

Over the course of the week, we needed to produce a design that included at least three parts:

• Bubble diagram (showing initial concept and connections)

• Garden masterplan, including a cross-section diagram

• Planting plan

The bubble diagram was to form the starting point of our design, as it is a way of arranging all the different spaces within the garden plot and looking at the relationships between them, without getting caught up in too much detail. All of the different components of our garden could be mapped out as bubbles within the plot, and we could consider how they would connect up, both visually and through movement of those using the garden. Here, we were using tracing paper over a fixed scale plan of the 25m x 20m garden, and we were using a freehand sketching style. As we considered which parts of the garden would or wouldn’t work well next to each other, and how they could be connected, we would discard and refine a bubble diagram, placing tracing paper over tracing paper, until we finally got to the space arrangement that we were happy with.

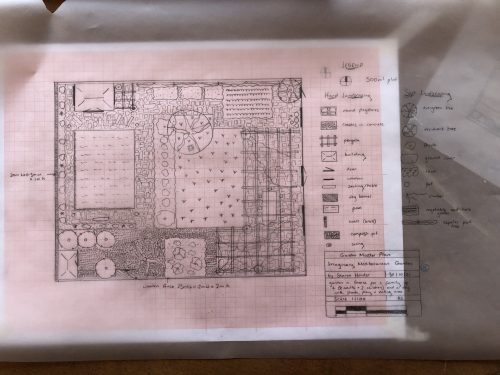

Lena then taught us how to work from our final bubble diagrams through preliminary designs that gradually would incorporate more and more detail right up to a master plan. We were taught the common conventions in garden design for representing different types of hard landscaping, buildings, different size plants, and were able to practise drawing these on our plans. Gradually our plans became more refined as we discarded tracing paper time and time again to whittle down our ideas into something that looked a bit more professional and workable! The final masterplans had all the hard landscaping detail, such as pergolas, paths, seats, compost bins, as well as indications of what types of planting would be where, such as key trees or border areas. The plans could be annotated and coloured to give extra detail and to bring to life the main areas of the garden.

Masterplan for my imaginary Greek garden

Cross-section diagram taken from the masterplan

As our masterplans were two-dimensional drawings, we were shown how to draw a scale cross-section diagram from various points on our plan, which would help to bring to life what the garden would look like from a particular viewpoint. In professional garden design projects, this would all be done digitally to produce a much more sophisticated projection of the garden, but we had a go at doing as good a representation as we could on paper!

Once we had created our masterplans, Lena encouraged us to start to think about the detail of the planting. We had several classroom sessions looking at Greek gardens that have recently been designed or redesigned to consider plants that would work well. We were also able to take inspiration from the landscape around us, our visits to other places in the local area, and the hotel’s extensive library on Greek flora. I was able to draw on my knowledge of the Mediterranean plants that we grow at Merton, and those I had seen growing elsewhere in the Mediterranean. It was very tempting to select a lot of plants that are personal favourites, but Lena encouraged us to think about how to create interest in all four seasons, to consider the maintenance of the plants, where the sun would fall, how plants would look and feel from a distance or up-close, and how big they would eventually get.

While we didn’t have the time to research costings of the plants in our design and consider the budget we would need for the creation of our garden, Lena talked us through the process of creating a budget and what to consider when working with local nurseries to obtain the plants.

Planting plan for my imaginary Greek garden

On our final day we had the opportunity to complete our garden designs, and to present them to the rest of the group. Although this was my first time at putting together any type of garden design, and although I felt out of my comfort zone at several points during the week, I was really surprised by how much I enjoyed the whole design process. I found that the process of sketching and drawing was really absorbing and strangely calming. Hours passed without any of us noticing! I enjoyed the planting plan the most – tackling the challenge of selecting plants that would grow in an unfamiliar climate and look good throughout the year.

Presentations of our garden designs

Our classroom setting

We were all aware that what we had put together over the course of the week was at a very basic level, and that the reality of designing and constructing a garden design from scratch would involve a lot more steps and expertise. We had a final teaching session that addressed some of these additional elements, including how to design construction plans and irrigation plans as well as produce maintenance and management plans for our gardens. The creation of a full garden design often needs a multi-disciplinary team, as the expertise of engineers, construction specialists, landscape architects and horticulturists will be required to do every aspect properly. Lena pointed out that the design process is a long and evolving process, with numerous plans and versions of plans being created. It doesn’t end once the garden has been created, as the management or maintenance plans will keep evolving as the garden comes to life.

Garden and landscape visits

During the week, the classroom sessions were broken up with visits to see more of the local landscape and some local gardens.

On the second day of the trip, a public holiday in Greece, we visited nearby Milies, a traditional Greek mountain village set on Mount Pelion. At this time of year, there was a very autumnal feel to the village, with beech and plane trees starting to turn yellow and lose their leaves. As in Lafkos, small courtyard gardens were the norm, with olive trees, climbers, succulents and herbs dominating, mostly grown in pots.

Platanus sp. in Milies square

Traditional village courtyard garden

The local railway station had a very forested feel, with Hedera helix and Parthenocissus sp. growing rampantly over abandoned buildings and lush green views out over the surrounding mountainside. Here we practised our freehand sketching, trying to capture perspective, some of us not as successfully as others!

Milies railway station

On our way home, we stopped at a stonemason’s situated near to a local quarry. We were able to see just some of the variety of hard landscaping materials available for Greek gardens, and the different sizes, textures and colours they come in.

Later on in the week, one of the course participants allowed us to visit his own home and garden, which he had recently moved into. Both the house and garden will be projects for him and his wife, and so we were able to look at the garden as a potential design project. They have a large site with plenty of established trees and shrubs providing shade, and with great views out to the hillside. However, the whole site is on a slope and the dominance of the largest trees, such as walnuts (Juglans regia) and false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia) would need to be considered in any new design.

View of the garden

Robinia pseudoacacia and garden terraces

On our penultimate day, we had the opportunity to visit the garden of a German couple living on the outskirts of Lafkos. They had an extensive garden set within olive groves, and it was a plot that they had been developing over the past 20 years. Keen gardeners, they make their own mulch by chipping all their garden waste (with the exception of weed seeds and roots) and adding this to horse manure, kitchen waste and ash from their fire. After six or 12 months, they have a fertile compost, which is laid over irrigation pipes on their beds and borders. By covering their irrigation pipes, they can ensure the heat of the sun doesn’t damage them.

Home-made compost

They have had great success and are able to grow a wide range of plants, despite their exposed and sunny hillside site. They grow their own beans, onions, courgettes, peppers, tomatoes and chillies, as well as a range of herbs such as sage, basil, rosemary and thyme. Their fruit trees include orange, grapefruit, clementine, mandarin, apricot, persimmon and pomegranate, and they also get a good crop of avocados and olives.

Persimmon tree

Ornamentally, the garden is full of interest and beautifully laid out to give interest around every corner. They have brought seed from Germany over the years and will try anything to see what will survive. A beautifully pruned Quercus coccifera provides shade over the outdoor eating area, while Callistemon and Bougainvillea provide colour and frame the view from this deck down to the coast.

Quercus coccifera

View from deck to the coast

Other interesting trees were Grevillea robusta (silky oak), Schinus molle (pepper tree) and Albizia julibrissin (silk tree). Plants that thrive in this garden seemed to be Bauhinia forficata, a shrub that was found throughout the garden, and Aptenia cordifolia, which formed a green and pink carpet of groundcover under many of the trees. They also had a wide range of bulbs, including Sternbergia lutea, Zephyranthes rosea and a range of orchids – flowering at this time of year was Spiranthes spiralis, the first time I had seen this very delicate but striking orchid in the wild.

Albizia julibrissin

Variety of trees in the garden

Bauhinia forficata

Spiranthes spiralis

Aptenia cordifolia

On the way back from this garden, we drove through the olive plantations down to the coast and the village of Melina. It was interesting for me to see the change in the landscape, from the lush, wooded area surrounding our hotel with its abundance of Arbutus, Cotinus and pines, to the silvers of the olives at lower altitudes and the Tamarix spp. on the water’s edge at the coast.

Transferring my learning to the UK context:

Plants that are most useful for Mediterranean / water-wise plantings in the UK

As mentioned, I was surprised by the number of plants that I saw growing in the Pelion that we are also able to grow in Oxford in the UK. This was a great indication that it is possible to grow a wide-range of plants in Mediterranean and dry gardens in the UK. The Pelion is only one area within Greece and its elevation gives it very different vegetation from some other areas, but a lot of the plants that we saw during the week can be found across Greece.

The types of plants that thrive in Greece are those that are adapted to survive through a long period of drought and many months of strong intense sunlight. In the Pelion, there are also strong sea breezes and increasingly colder winters (with occasional frost and snow) for the plants to contend with. Common plants are therefore those with adaptations that allow them to survive year-round in these conditions – for example, grey, hairy or small leaves to reflect sunlight and reduce water evaporation, tough leaves to cope with the strong sunlight and wind, and strong or double root systems.

Silver and small-leaved plants growing in the hotel garden

Arbutus unedo growing in Lafkos

In terms of trees, Quercus coccifera, Ficus carica, Arbutus unedo, Eriobotrya japonica and various pines were all seen in abundance along the roadsides and in gardens, and these are all plants that we are able to grow at Merton. Likewise, Cotinus coggygria and Pittosporum tobira were also a common sight, sometimes as shrubs and sometimes grown as trees – plants that provide us with autumn and winter interest in the UK respectively.

The common climbers in the Pelion, Trachelospermum, Wisteria, Parthenocissus and Jasminum spp., all grow happily in many areas of the UK on south-facing and sheltered walls.

Lavandula angustifolia, Rosmarinus officinalis, Nerium oleander and Callistemon spp. were shrubs that we saw frequently over the course of the week – many of these have either the silver or fine leaves designed to help them cope with the hot and dry conditions. In Oxford, we grow varieties of lavender along an exposed southerly terrace, and Callistemon in a south-facing sheltered spot. These are permanent plantings, however our Nerium plants have to be over-wintered in greenhouses for us to ensure that they will survive the winter.

Perennials and annuals that I’ve encountered in both the UK and the Pelion include Gaura lindheimeri, Salvia spp., Sedum spp., Euphorbia caracias, Euphorbia dendroides, Tradescantia and Tagetes. My fellow course participants spoke of the increase in the popularity of grasses in Greek gardens, something that we have also seen in the UK. This is another group of plants that can do well in water-wise plantings.

Gaura lindheimeri growing in the hotel garden

Top design features to take into consideration in planting a water-wise garden

Several key features stood out from the classroom teaching I received and also from my observations in the gardens that we visited. These were:

Water harvesting: In Mediterranean climates, water is scarce at certain periods of the year and so has to be used wisely. Incorporating drains and water butts into a garden design is vital in order to harvest the rain when it does come for use at other times in the year.

Right plant, right place: It is important to select a palette of plants that will thrive in the garden you are designing. If a garden will receive little rainfall and will receive minimal additional irrigation, the plant selection must bear this in mind. This must be considered for all types of plants that are being incorporated in the design, from trees through to annuals and bulbs.

No-water/low-water zones: It may be the case that a completely dry garden is neither practical nor desirable for some garden designs. In these instances, to keep the design water-wise, it is important to create a planting plan where plants are grouped together depending on the amount of water they need, thus creating different zones within the garden. While some of these zones may require some irrigation, such as a vegetable patch or nursery area, ideally there will be other zones that require no irrigation at all once the plants are established, and other zones that require very minimal additional irrigation. For practical reasons, it is often most appropriate for the no- and low-water zones to be furthest away from a house, while plants that need some watering to be grouped nearest to the house.

Paving / lawn alternatives: While grass lawns have long been incorporated into gardens around the world, it is easy to see that they can be problematic environmentally and in terms of water conservation, especially in a Mediterranean climate. Therefore, it is worth considering how much of the garden could be paved, as is very common in many Greek courtyard gardens, and what type of paving would be most appropriate and aesthetically pleasing. If a lawn is specifically requested in a design, it is worth considering alternatives to grass. There are a number of ground cover plants which withstand drought well and which therefore could be used to create a non-grass lawn. These include Dymondia margaretae, Achillea crithmifolia and Phyla nodiflora.

Paved courtyard garden in Melina

Mediterranean non-grass lawn

Shading: Shade is a vital element in a Greek garden, allowing the garden to be used at all times of year and day. Climbing plants and trees are often used to create the shade, and those with a dense canopy of leaves can create shadow that shelters plants placed underneath them from the intense heat, such as pot plants.

Pergolas and climbing plants creating shade in Lafkos

Most useful learnings for the UK context

Although the course took place in a landscape that was completely unfamiliar to me, the teaching that I received was highly applicable to the UK and I felt that I would be able to use what I was learning to inform my work. Having seen the broad overlap between plants grown in the Pelion region and those grown in Oxford, I would now feel more confident with trying out a broader range of Mediterranean plants in personal and future gardens I work in. The introduction to creating and drawing a garden design from scratch was a great starting point from which I can now feel more confident to look at small garden spaces afresh and to bring my own design ideas to them.

One of the most striking things that I learnt from the week was the all-encompassing and holistic nature of garden design. It is not something that takes place in an isolated space – instead it needs to be informed by the way the space is currently used, by the landscape around it, by the wishes of those who will encounter it and use it in future. A garden design doesn’t exist as simply a two-dimensional paper plan – rather a full design process consists of numerous plans which are influenced by culture, society and time, which evolve through a series of conversations between a range of people, and which will be brought into actuality by a multi-disciplinary team. As I take what I have learnt forward, I hope that I will hold the importance of this ’bigger picture’ approach in mind.

Conclusion

This week of garden design teaching was a wonderful introduction to an area I really wanted to learn more about. Through the classroom sessions and practical exercises, I was able to gradually gain confidence in the subject matter as I took in the teaching through the week. Having practical drawing exercises and tasks to complete meant that I was able to try out what I was being taught and consolidate new skills. I hope that I can take what I have learnt and build on it as I go forward in my day-to-day work as a gardener.

To be able to undertake this course in Greece was a wonderful opportunity to see a whole new region of the Mediterranean and the flora that grows there. I was able to see plants that I was already familiar with in a new light, and take inspiration from plants that I came across which were new to me. Although there wasn’t the time to properly explore the region or botanise much, the week definitely sparked a personal interest in Greece and I hope to be able to return soon to explore its landscape and gardens much more!

View of Lafkos village

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to MPG for very generously supporting my trip through provision of a bursary. In addition, the Great Dixter Charitable Fund supported me with a Christopher Lloyd bursary. These bursaries made it possible for me to meet the costs of the course and participate in this training – without them I would not have been able to travel. A huge thank you to both organisations.

I am also very grateful for the intensive teaching given by Lena Athanasiadou who worked extremely hard throughout the week to impart as much information as she could. Thanks also to the Lagou Raxi Hotel in Lafkos, my fellow course participants for making it a very collaborative experience, and those who generously allowed us to explore their gardens.