Western Australia – Kings Park and Bushland

Matthew Bryant 2022

Xanthorrhoea sunset

Introduction

I am a horticulturist at The National Botanic Garden of Wales with a particular interest in Mediterranean flora, especially Western Australian flora. Following this passion has led me to work within the Great Glasshouse – the largest single-spanned glasshouse in the world, situated in rural Wales. It houses plants from six different Mediterranean regions of the world; the largest area of coverage within the Great Glasshouse being the Western Australia section. In September 2022, I was given the opportunity to take up a placement with the Western Australian Botanic Garden at Kings Park in Perth. With plans to redevelop the Great Glasshouse at NBGW, not only was this trip a dream come true, but also very important, as nothing beats seeing flora in situ.

Aims and objectives

- Develop my knowledge in propagating and establishing Western Australian flora

- Increase knowledge of Western Australian genera

- Gain ideas for planting schemes by seeing plants in situ

- To share knowledge with fellow horticulturists

Kings Park

Unlike The National Botanic Garden of Wales and most other botanic gardens, Kings Park is focused solely on flora native to Western Australia. With 13,000 native species, many of which are endemic, they have plenty to choose from. This makes Kings Park the perfect place to learn about Western Australian plants. Consisting of 400 hectares, two thirds of which are protected bushland, Kings Park provides a green haven at the heart of Perth.

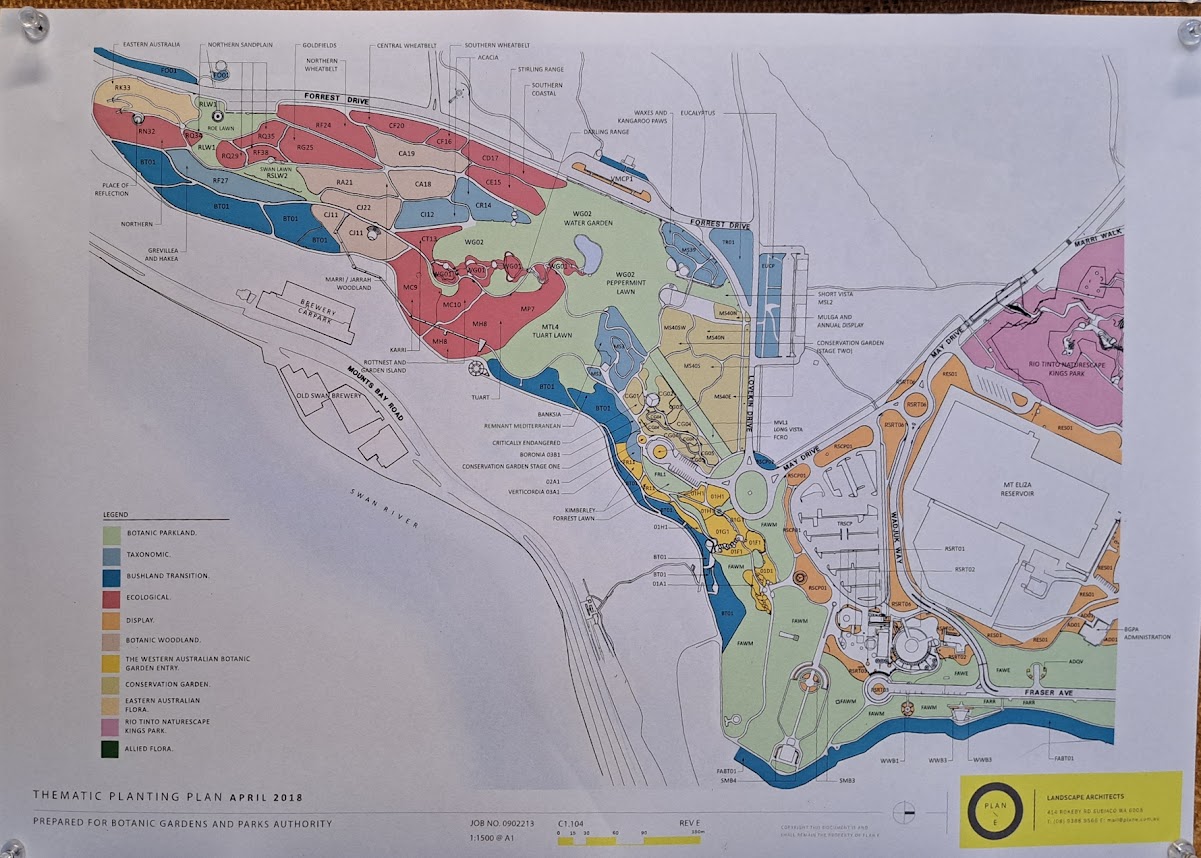

Map of King’s Park

King’s Park display

The journey started with getting to Heathrow airport, which is harder than you think coming from rural south west Wales, especially when your train is cancelled last minute and you have to book a bus, and sort out a lift to the bus stop at 2am. After a long day of traveling, I finally landed in Perth, Australia! Even before getting through customs, I remember getting excited by a Xanthorrhoea I spotted through the window. My luggage on the other hand didn’t make it to Perth with me; it failed to catch the connecting flight in Kuala Lumpur. The only information I could get was that my luggage would be with me within a week. After locating and checking into my hostel, I went out to buy some essentials since mine were somewhere in Malaysia.

Week One Highlights

I spent my first week on placement with the propagation team at Kings Park. I learned so much during this week, including learning about genera I didn’t know existed, propagating techniques I never considered and some brand-new ones to me. I also got the pleasure of meeting a friend’s dog. All in all, a great week.

Propagating techniques

One technique I never considered when it came to our Mediterranean collection is grafting. We do this regularly at NBGW with our fruit trees, but never with anything else. The main reason they graft at Kings Park is to grow flora that wouldn’t necessarily grow in Perth, so they use root stock that is well suited for Perth’s climate. Kings Park have two techniques for grafting; the standard way and the “mummy” way.

The standard method:

- Match your grafting material with a similar width rootstock cut at said width.

- Then using scalpel slice the end of the grafting material into a “V” shape ensuring to get a uniform shape.

- After this use a safety razor to slice down the middle of the rootstock the length of the “V” you’ve just created.

- Then gently join the two together securing them in place by wrapping in grafting tape twice.

- Cut foliage back to reduce transpiration.

- Place in a fog unit (high humidity reduces transpiration)

Grafting

For the mummy method follow step 1 to 3. Then cut all the foliage off, wrap the join and all grafting material in one layer of grafting tape, then place in a hot greenhouse 40°C – 50°C. The theory is the heat stress causes the graft to take and for the nodes to break through the tape. Apparently, this was discovered after someone left a graft in their car on a hot sunny day.

Another method I found interesting is the pre-treatment for cuttings. They get soaked in a 50:50 Aspirin and Rhizotonic solution for 15 minutes. They are then dipped in Clonex and put into the appropriate growing medium. For arid plants they use rockwool which ensures the cutting has constant access to moisture but not enough to cause it to rot.

Cuttings in rockwool

Week Two Highlights

The second week started with a trip to John Forrest National Park which is Western Australia’s first national park. Here I got to see many species that I care for in the Great Glasshouse in situ, including Darwinia citriodora, Hypocalymma angustifolium, Calothamnus quadrifidus and Lechenaultia biloba. As well as many other species I would love to have in our collection, such as Drosera glanduligera and Banksia sessilis.

Drosera glanduligera

Calothamnus quadrifidus

Banksia sessilis in John Forrest

Lechenautia biloba

Hypocalymma angustifolium

Seed processing

I then got the chance to help collect and process the seed of one of my favourite plants – Banksias that we collected from the different species within the garden: Banksia nivea, B. brownii and B. epica. After collecting the seed pods and the whole specimen of B. nivea, we took them back to be processed. One of the many cool things about Banksias is their relationship with fire that the majority of them need to survive. This means in order to harvest the seeds from the pods, you have to set them on fire to mimic a bushfire, and then submerge them in water to mimic rain – this is exactly what we did to the pods of B. epica.

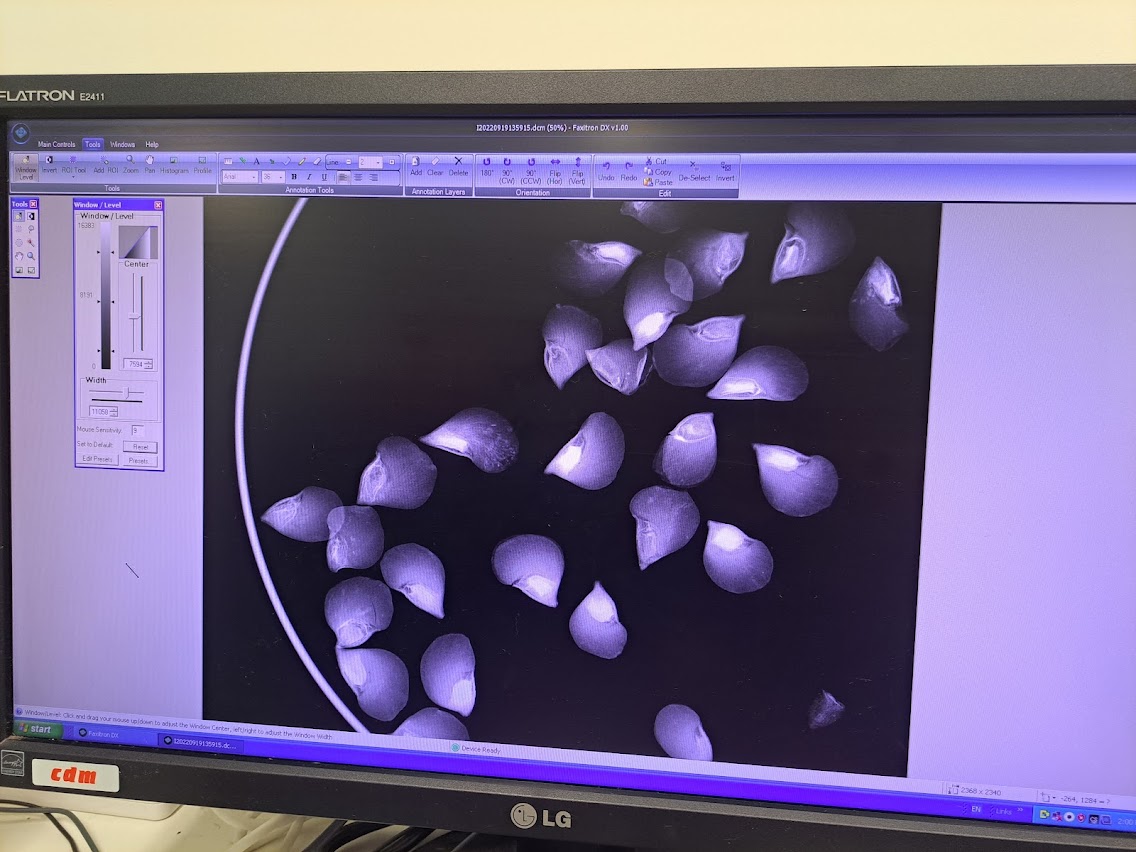

Kings Park also run germination tests on all the seeds that they collect, by x-raying the seeds and selecting the ones with the most intact and full embryos. Then, ideally 100 of those are sown in an incubator. This will then provide them with the percentage of successful germination rate.

Collecting Banksia epica pods

Burning Banksia pods

X-raying Banksia seeds

Week Three Highlights

Week three didn’t go as planned but in a great way. I was originally meant to go on a solo trip down South. However, an opportunity arose to join two fellow horticulturists on a road trip up north to look at wildflowers. As it was spring, this was the perfect time of year to go in search of wildflowers – how could I say no to this! So, I decided to extend my work placement by a week and join Pascarl Purser from Kings Park and Catherine Cutler from the Eden Project on an adventure up north. Catherine is a fellow member of MPG, who was in Australia to attend the Global Botanic Gardens Congress in Melbourne.

The highlight of this trip by far was visiting Lesueur National Park. The biodiversity in this park is incredible – it holds 10% of all known Western Australian flora, including nine species that are endemic to the park. Even before arriving at the park, we spotted lots of interesting flora growing on the side of the road, such as Verticordia grandis, and had to keep reminding ourselves not to stop every five minutes as we hadn’t actually arrived at the National Park yet. Once we arrived at the park, we set out to do one of the circular hikes; on this hike I saw so many interesting things, most of which I’m yet to identify. I finally got to tick a plant off my plant bucket list: Nuytsia floribunda, the world’s largest parasitic plant – its adapted roots have blades for slicing into the roots of other plants. Other highlights included the black kangaroo paw Macropidia fuliginosa and seeing Allocasuarina sp. flower for the first time (it’s nothing like what I would imagine it to be).

The rest of the trip consisted of visiting amazing places seeing wildflowers and other flora in situ, and getting inspired for ideas of planting schemes to bring home. Here are some of the highlights of my favourite finds of the week:

Verticoria grandis

Macropidia fuliginosa

Nuytsia floribunda

Lesueur National Park

Lechenaltia macrantha

Allucasuarina sp

Map of Northern roadtrip

Map data ©2023 Google

Week Four Highlights

Week four was also sadly my final week of placement, and was all about looking at plants in situ to get ideas for the Great Glasshouse. With the south-west of Western Australia being recognised internationally as one of the biodiversity hotspots of the world, as well as being a relatively high humidity area, it would be an ideal range to try and recreate/conserve in the Great Glasshouse.

The week started with picking up my transport/home for the week – a little campervan I named Allan. After acquiring Allan and then navigating the roads out of the city of Perth I did a big food shop and then set off on the main leg of my journey, nearly a four-hour drive to the first campsite (for reference that’s about the time it takes to drive the length of Wales). After arriving and checking into the campsite I went to stretch my legs and just in front of where I parked spotted a donkey orchid, Diuris sp. in the campground!

Donkey orchid

Allan the camper

The trip consisted of visiting three main sites with little detours in between. The main stops were the Stirling Range National Park, Porongurup National Park and the Valley of the Giants.

The Stirling Range National Park

The park is home to well over 1000 species of plants including a few that are endemic to the area. To take in all of the Stirling Range I decided to hike to its highest point – the summit of Bluff Knoll. With a prominence of 650 meters, it is an impressive sight. The hike consisted of amazing views and fascinating plants, as well as the odd curious lizard. The lower parts are a forest of Eucalyptus and Allocasuarina; at this level I was fortunate to spot two orchids Cyanicula sp. and Caladenia sp. As I hiked up, the canopy lowered and became shrubbier – the shrubland included Acacia sp., Gastrobium sp., Leucopogon sp. and Xanthosia rotundifolia. The summit provided amazing views of the Stirling Range, almost popping out of the nearly perfectly flat surrounding landscape.

Cyanicula sp

Gastrolobium sp

Kunzea montana

Xanthosia rotundifolia

Bluff Knoll

View from summit of Bluff Knoll

Bobtail lizards

Banksia gardenri

Leucopogon sp

The Porongurup National Park

The park is known for its giant ancient granite rock formations. I went on a couple of hikes; one up to Castle Rock and then a circular walk around the lower parts of the park. While the first hike provided amazing views of the landscape and the granite rocks were impressive, I found the lower hike to be more rewarding, walking amongst the tall karri trees, Eucalyptus diversicolor. These impressive trees provided shelter for a thriving undergrowth. One of the highlight plants among the undergrowth was the tassel flower, Leucopogon verticillatus. Before going on this trip, I hadn’t heard of this genus which is in the Ericaceae family. This particular tassel flower is used by the Noongar people as a bush food with its edible berries as well as damper bread from its dried seeds. This would be a great plant to get in the collection to educate people on the ethnobotany of Western Australia. Other things that caught my eye in the undergrowth were the karri hazel Trymalium odoratissimum subsp. trifidum, tree hovea tritium elloptica and a curious wallaby.

Eucalyptus divesicolor

Trymalium odoratissimum subsp trifidum

Leucopogon verticillatus

Hovia elloptica

Wallaby

The Valley of the Giants

My final main stop was the Valley of the Giants and here I was blown away by how big some Eucalyptus trees can get, over 70 metres tall! Here I not only went for a hike under these magnificent trees but also among them on a 40-metre-high walkway. Many of these trees have been hollowed out by insects, fungi and fire leaving these amazing living structures. I’ll let the photos do the talking…

Tingle forest canopy

Eucalyptus guifoylei

Eucalyptus jacksonii

Eucalyptus jacksonii

Cryptostylis ovata growing on an Allocasuarina sp

Allocasuarina decussata

Conclusion

This trip was an amazing once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and it far exceeded my expectations and fulfilled my aims and objectives. I met some inspiring and passionate people who were more than willing to share their knowledge with me. I learnt so much about genera I didn’t know existed and propagation techniques for flora we have been struggling to establish. Seeing plants in situ was by far the best aspect and has truly inspired me and given me some great ideas for the Australian section in Wales. I’m hoping I will get the opportunity to follow these through and share the knowledge I’ve gained with my fellow colleagues, students and members of the public.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone who made this trip possible and supported me. Mediterranean Plants and Gardens and The Royal Horticultural Society for funding the trip; The National Botanic Garden of Wales for giving me the time to go; Kings Park Botanic Garden for allowing me to visit, and all their staff for being so welcoming and friendly, especially Pascarl Purser for being a brilliant host, tour guide and friend.