Second tour of the gardens of Lazio, Italy

Monday 30 September – Monday 7 October 2019

Following the success of the MPG Lazio tour in October 2018 and the high demand for places, this tour was essentially a repeat but a day longer with three nights based at Hotel Viterbo in the town of Viterbo and four nights at Hotel Cacciani in Frascati. Additional locations visited were Viterbo Botanic Garden, Castello Ruspoli in Vignanello and the Apostolic Palace at Castel Gandolfo. Again, Christina Thompson, MPG member and resident of Viterbo, acted as guide for the tour.

The Pope’s Summer Garden

The countryside approach to Viterbo appeared lush and green, a combination of rich volcanic soil and recent September rainfall. Although holm oak is endemic, the tree cover here is largely deciduous and not at all what many normally associate with Mediterranean areas. The trip began on the way in to Viterbo at Botanic Garden ‘Angelo Rambelli’, a relatively new botanic garden which dates from 1991 and covers six hectares west of Viterbo. Former wasteland – which still borders the garden – now hosts many thousands of plants, including a rose garden, a palm grove, an area of Mediterranean maquis and an area of desert succulents. Mineral vents discharge hydrothermal liquids feeding attractive ponds and giving rise to areas of travertine rocks which support drought tolerant plants such as the locally rare Santolina etrusca. Nearby there were abundant autumn crocus, autumn cyclamen and Artemisia arborescens.

Monday evening then involved a coach outing from Hotel Viterbo to a very memorable wine tasting, cellar tour and dinner at the family-run cantina of Sergio Mottura in the village of Civitella d’Agliano.

Agave attenuata

Maclura pomifera or Osage orange

Albizia (silk trees)

Viterbo Botanic Garden

Day Two

Castello Ruspoli, Vignanello, still under private ownership

Tuesday began with a visit to Castello Ruspoli in the historic hilltop village of Vignanello. This location displays a locally common layout of: ridge town → square → fortified house → ordered garden → wild garden, countryside. We enjoyed a guided tour of the castle which is built on the elevated site of an earlier Benedictine monastery. A stone drawbridge leads from the rear of the castle across to a formal parterre garden which dates from 1610, this being rather late for its Renaissance style. The artificially raised site of the formal garden is subdivided into twelve square patterns around a central fountain. Each square is bordered by hedges of large box and other evergreen shrubs, with lower interior hedge patterns formed from dwarf box. The sides of the parterre away from the house are bordered by tall shrubs and trees with small ‘wild gardens’ irregular in shape beyond to the north and east and a small parterre, a secret garden, on the (lower) south side.

There are around 500 large pots laid out across the main parterre, mostly containing lemon trees or hydrangeas. The principal gardener, who has 48 years’ service, kindly demonstrated his technique for manually scything the hedges, a task he told us he completes every ten days in summer.

Church in Vignanello

Head gardener talking to Mona over the box hedge

We then moved to Caprarola for lunch at Trattoria del Cimino da Colombo and then a visit to Palazzo Farnese above the village. This incredibly impressive palazzo and accompanying gardens were largely constructed by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, a grandson of Pope Paul III, in the 1550s. The palazzo is in the form of a pentagon constructed around a circular colonnaded courtyard with a sequence of exquisitely ornate and decorated grand rooms, one incorporating a large grotto and another bedecked with large painted maps of the 16th century world.

Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola – Renaissance Mannerist construction

The Secret Garden, Palazzo Farnese

To the rear of the palazzo a drawbridge leads into an extensive set of gardens rising up the hillside, much being designed in the Mannerist style. Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola designed the two gardens around the Palazzo, the winter and the summer gardens. The upper gardens were designed and built slightly later.

A long and stepped staircase leads through a range of garden styles, structures, statues and plantings, with variation in pattern and far less symmetry than seen previously at Castello Ruspoli. Water features and tricks of perspective and expectation abounded. We were told that some areas would originally have contained flower and fruit plantings, although no traces survive. As with the gardens at, say, Stowe in England, considerably more time would be required to take in and to fully understand the symbolism and significance of what we so quickly saw. Also, one could but wonder how such a great palace estate – private gardens displaying great wealth and with multiple references to classical Roman and Greek heroes and gods – matched the stated contemporary religious messages of the Counter-Reformation and the Inquisition, ordered and led by the very cardinals and popes which included members of the Farnese family!

We returned to Viterbo where, thanks to Professor Goffredo Filibeck, we had the use of a room in university buildings close to our hotel where tour guide, Christina Thompson, gave an illustrated lecture: ‘Mannerism in late Renaissance gardens’. Mannerism linked the times and styles from Renaissance to Baroque. In late 16th century gardens it represented a move away from formality and typically incorporated a mixture of asymmetric patterns, classical references, water features and attempts to surprise, trick and entertain the visitor. However, symmetry is still a key element, reference Villa Lante where even the ‘palazzo’ is divided into two palazzetti to make the garden perfectly symmetrical.

Day Three

Wednesday began at Villa Lante in the small town of Bagnaia, considered by some to be the finest example of a Mannerist garden. It was begun in the 1560s by Cardinal Francesco de Gambara, the then Inquisitor General. The modern entrance from the town is a side entrance from beside the original wild garden, itself effectively a 16th century public park for the town, albeit a park which included features ranging from simple stonework to elaborate sculptures, water features and a Pegasus fountain. Once through the side entrance, Christina encouraged us to walk up through the inner garden with eyes lowered until we neared the original, upper entrance where we turned and could then begin our visit as the first owner intended.

As the visitor descends from the original entrance, the gardens unfold in a series of scenes depicting the passage from nature to civilisation. The palazzo or villa itself is actually formed of two small casini (houses), built 30 years apart and positioned part way down the park. There are water features and fountains throughout the descent: fountains with dolphins representing the sea, fountains with lounging statues of the gods of the rivers Arno and Tiber, a table of water and a fountain of candles. At the lowest level are the largest water spaces, including carved miniature stone ships on a lake.

Banquet table

There are visual puns on the de Gambara family name throughout, including multiple low-relief prawns (gamberi) and a water-chain composed of a strangely elongated prawn ending in a massive pair of claws.

Water chain at Villa Lante

After a walk around the ‘wild garden’ we beat a hasty retreat as a downpour began with lunch awaiting in one of the town’s restaurants.

Bangnaia walk to lunch

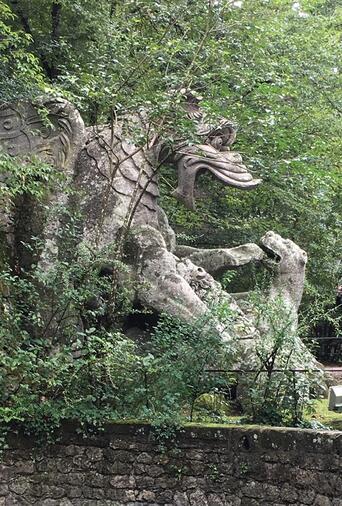

We then moved to Bomarzo, the site of the Sacro Bosco (= Sacred Wood) garden. This garden was designed in 1552 by Prince Vicino Orsini, a reluctant soldier whose career had ended with a long period of captivity abroad when the then Pope snubbed him and his family by refusing to pay the requested ransom. After a long period of neglect, this ‘garden of monsters’ has inspired twentieth century visitors and artists such as Salvador Dali.

Again the modern entrance gave little clue as to what lay ahead, a long approach led into the wild garden and passed a succession of increasingly strange sculptures: two sphinxes (not in their original positions), two giant wrestlers, a giant tortoise supporting an ornate column (an allegory of fame), an avenue of standalone classical columns…. And then, a small house that challenged the senses: one entered and climbed a floor level in a building where no floor seemed to be horizontal and no wall seemed to be vertical.

One then exited into the ‘real’ garden, a garden of incredible sites and mixtures of scales: round each turn were carved rock shapes, an elephant battling a Roman soldier, a row of great urns, Greek gods, giant pine cones , huge mythical beasts, columns, a gaping mouth fronting a cave, bears etc, the last mentioned punning on the founder’s name. Then, finally, as the senses returned to normal, we reached a small classical temple, a mausoleum for Orsini’s wife.

Afterwards, an evening meal of multiple piscatorial delights was enjoyed at l’Altro Gusto, a restaurant within the walled old town area of Viterbo.

Day 4

Thursday saw an early departure from Viterbo and onto the motorway for the move to Hotel Cacciani in Frascati with en route visits to Hadrian’s villa and nearby Villa d’Este in Tivoli.

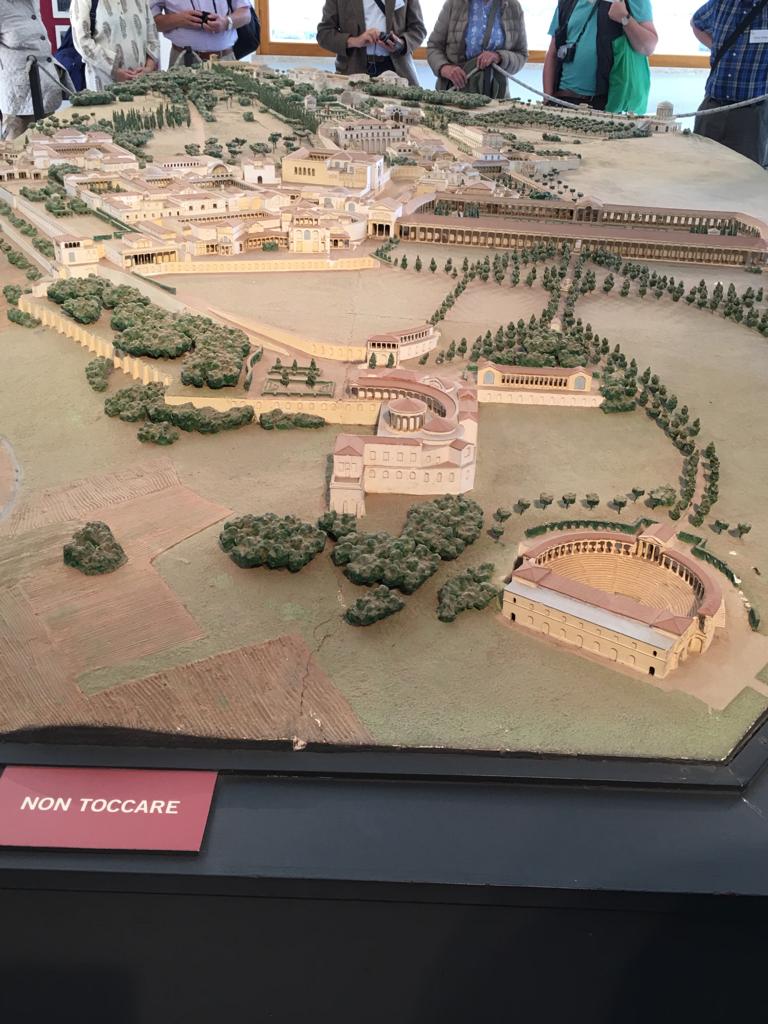

Hadrian’s villa became the emperor’s official residence around 128 AD. The site is vast, an onsite model showing it to have been constructed on the scale of a fair-sized town, albeit with an inordinate number of very grand buildings. Christina took us to three specific areas before encouraging us to explore the rest of the site.

We went first to the expanse of water known as the Pecile, a huge porticoed area – based upon a traditional Roman Stoa – surrounding a garden and rectangular central pool. Today the vanished columns are successfully replaced by columnar bay trees. Then the so-called ‘Maritime Theatre’, actually believed to be the site of the emperor’s private rooms. Its circular construction, ringed with a moat, can be traced in many later circular fountains, including at Villa Lante. Thirdly, we looked at the Canopus, featuring a domed dining pavilion at one end of a long pool of water and the remains of a colonnade at the other. This had caryatids replacing some columns and was decorated with numerous statues. The high stone banqueting couch surrounding the pool suggests a luxurious summer dining room for the emperor and his entourage. Sculptural and design references to areas of the Roman Empire frequented by Hadrian abounded, these including many Greek and some Egyptian items.

As we walked we could recognise items we’d seen as inspiration for sculptures and structures in 16th century gardens on the previous two days, the link being that the first major excavations at this site were carried out under the auspices of early 16th century popes and hence would have acted as models for the wealthy families of the Papal States when laying out their garden estates in the following decades.

We next enjoyed an alfresco lunch at Restaurant Sibilla in the town of Tivoli, the restaurant being located on a terrace alongside Parco Villa Gregoriana, a viewing platform constructed in the second century BC to support two temples of Vesta.

Then a short walk to Villa d’Este, a fabulous hillside estate, begun c1565 by Ippolito d’Este, Bishop of Ferrara, Governor of Tivoli, grandson of a pope and son of Lucrezia Borgia. Ippolito was fortunate in his domain including the site of Hadrian’s villa, then being excavated by his architect Pirro Ligorio, and many of the statues found there were taken and displayed at Villa d’Este and its gardens.

The complex plan of the area closest to the villa gives way – across a steep slope – to the more open and formal lower areas of the site, displaying many typical Mannerist features throughout.

Everywhere there is dramatic use of water, hydraulic engineer Alberto Galvani having diverted water from the Tiber through a multitude of channels, fountains and features, with grottoes, loggias and viewing terraces. Highlights include the terrace of the Hundred Fountains and the Fontana dell’Organo, the former showing amazing scale and the latter combining air and water power to awe the onlooker.

Day 5

Friday began with a later start than expected. Nevertheless, the day was completed as planned, although running behind schedule.

The first call was Ninfa, an eight-hectare garden begun in the 1920s by Gelasio Caetani across the ruins of a long-abandoned village that had been overwhelmed by nature and swamp.

Two generations of the family created a surprising garden with substantial English-style plantings against the background of a sheltering escarpment. The family planted trees and shrubs that have grown hugely in such favourable conditions.

As seemed to be the case at several sites we visited, the new entrance (into a wild area of ruined church buildings and occasional modern plantings) gives a very different impression upon arrival to that originally intended. From the decaying ruins visitors move onto paths, lawns, tree plantings, a large herbaceous border, a lavender-lined path and much, much more. Everywhere were roses. Around one corner was a grove of bananas beneath a soaring stone pine; elsewhere a small bamboo jungle. Water features are everywhere: channels, ponds, even a water channel constructed to flow above another water channel. Is this perhaps a 20th century interpretation of Mannerism? Some loved this; others had reservations about elements of the style, some of the plantings or the current approach to maintenance in some areas.

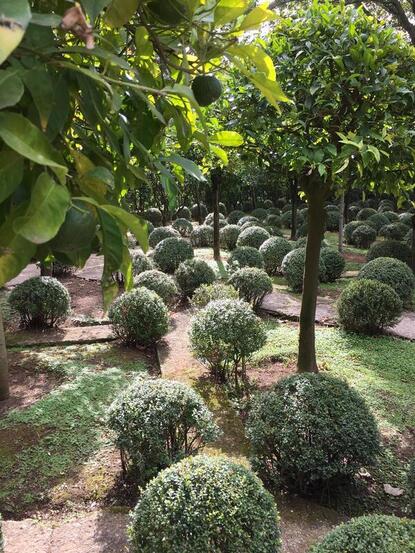

At the end of the tour we were fortunate to be invited to view a normally private walled garden area with a citrus orchard and some more traditionally modern Italian garden features close to the family home.

Lunch was then enjoyed outdoors at a restaurant in the delightful hillside village of Sermoneta. Our later morning start precluded spending time to fully appreciate the village itself and we left for our afternoon visit to nearby Villa Torrecchia where an enthusiastic and very knowledgeable young guide welcomed us.

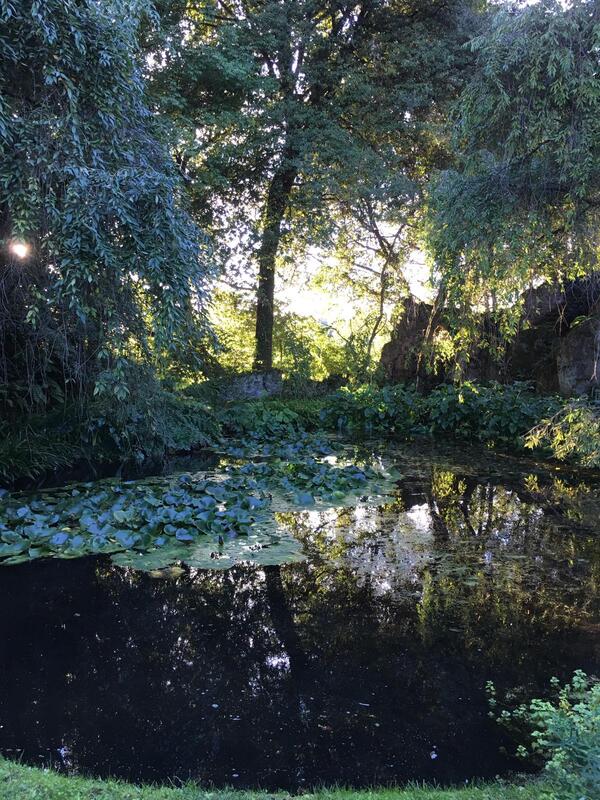

The garden of Villa Torrecchia is, like that at Ninfa, constructed on the site of a deserted village perched on the top of a hill and has several references to design elements seen at Ninfa. It is the centre of an agricultural estate bought in the 1990s by the late newspaper proprietor, Carlo Caracciolo and his wife Violante Visconti. Lauro Marchetti began the 18-month-long task of clearing the overgrown site and is responsible for the new trees, many of which were brought in as well-established plants, including the many camphor trees and the contorted pomegranates which surround the inner courtyard. Violante Visconti then called in Dan Pearson who devised a plan for the garden. The planting around the villa is formal, with neat pillows of box beneath the pomegranates, and a series of ‘rooms’ and open spaces with views over the countryside below.

Many roses came originally from Hillier’s – ‘Madame Alfred Carrière’ features – and the walls and pergola support enormous white Wisteria sinensis. Maintenance and development of the garden has continued under guidance from Pearson’s pupil, Stuart Barfoot, with additional rose plantings including ‘Rêve d’Or’ and David Austin cultivars such as ‘Jude the Obscure’. A particularly extensive wisteria covers the wall in an enclosure with a dark pool, which in spring and early summer is surrounded by annuals. Unlike Ninfa, there is no large source of water and a 170-metre well was sunk with the water that circulates in channels and ponds pumped for recirculation. Also, in contrast to Ninfa, with its open and sunny expanses of flowing water, the overall effect at Torrecchia is more enclosed, secret and, to some extent at least, more closely designed and maintained.

Day 6

Saturday was spent at Castel Gandolfo, until recently the traditional summer home of the Pope, with the Apostolic Palace looking down across volcanic crater Lake Albano and, nearby, the formal papal gardens along a hillside. Although the palace is located within the borders of Castel Gandolfo, it has extraterritorial status as one of the properties of the Vatican and is not under Italian jurisdiction.

The morning was spent visiting the palace which is now open as a museum, primarily telling the story of each pope from the current viewpoint of the Catholic church. We were led by our individual audio guides which did not explain the history of the building, but it appears that much of the grandeur we saw, and that popes once enjoyed, was lavishly restored around 1930.

A buffet lunch was then enjoyed in the large catering area for visiting groups within the papal Barberini gardens, although most were surprised at the quantity of throwaway, single-use plastic cutlery and crockery.

We then toured the papal summer gardens, largely recreated in the 1920s and 1930s upon the sprawling ruins of a residence of the Roman Emperor Domitian. Firstly, we saw a large area of hillside parkland with many mature trees, including delightful umbrella pines and smaller areas of formality containing sculptures and borders, often of hydrangeas. Around many a corner and under the man-made hillside cliffs were substantial remains from Domitian’s palace. Then, a prospect opened over the most enormous parterre below us: a vast terrace of green hedges and a multitude of bright bedding plants; the first time in the tour we had seen such colour and, indeed, so many flowers. Restoration across the parterre and its own retaining walls and structures looked almost complete and the high maintenance standards suggest considerable continuing expenditure. Everywhere the statuary was Classical, not Christian.

Berberini gardens at Castelgandolfo

Day 7

Sunday was our final, and short, excursion to Villa Landriana, the site this day of a busy plant fair.

Giardini della Landriana

Villa Landriana, the orange garden

The garden covers over ten hectares within a large estate, bought at the end of the 1950s by the family which still owns it. The gardens, designed by Russell Page, were divided into 30 rooms. These have since been extended and modified with new collections of plants, including heathers, hydrangeas, old roses and camellias, to satisfy the passionate botanical curiosity and aesthetic sense of its creator, Lavinia Taverna.

This guided visit produced mixed responses from the group – half thought it one of the most beautiful of the gardens visited, but for others the hungry mosquitoes were an incentive to move quickly through the space. A visit to an Italian plant fair was throughly enjoyed, although purchasing plants was not really an option for most, some succumbed which perhaps resulted in some difficult packing decisions.

Free time back in lively and historic Frascati was followed by our final dinner at Ristorante Cacciani in Frascati before we returned home or travelled onwards the following morning.

Many thanks to Heather Martin for planning such a great trip.

Geoff Hughes

photos: Anne Rendell